The Kuhl Irrigation System of Kangra: An Assessment of Himalayan Agricultural Heritage Using the GIAHS Framework and Literature Evidence.

DOI:- https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12452.13440, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17153175

Abstract

The Kuhl Irrigation System of Kangra represents a century old, community managed gravity irrigation network in the Western Himalaya. Integrated within the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS), it supports sustainable food production, biodiversity conservation, and cultural heritage across a diverse mountain landscape. Using the FAO’s Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) framework, this study evaluates the KAS against five core criteria: landscape features, food and livelihood security, agro-biodiversity, traditional knowledge, and cultural values. Based on field observations, GIS analysis, and literature synthesis, findings confirm that the system meets all GIAHS inclusion requirements. The Kuhl irrigation system embodies adaptive engineering, participatory management, and socio-ecological resilience, offering a global model for sustainable agriculture in fragile mountain environments.

1. Introduction

The Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) initiative, launched by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2002, recognizes agricultural systems of outstanding global significance that demonstrate a long-standing and harmonious interaction between people and their environment. These systems sustain food security, biodiversity, and cultural continuity across generations. As of 2025, there are 102 designated GIAHS sites worldwide. China leads with 25 sites, reflecting strong institutional support for heritage agriculture, while India with an area of 3.29 million km² has only three recognized sites, despite its immense agricultural diversity.

The present study evaluates the Kangra Kuhl Irrigation System not merely as a traditional water management practice but as a regional landscape of human environment co-evolution and sustainability. It seeks to position the Kuhl system within the GIAHS framework, emphasizing its integrated role in ecological adaptation, community governance, and long-term resilience of Himalayan agriculture.

The KAS is composed of three components namely Kangra Outwash Plains, Kangra Kuhls and Community Management(Kumar, 2025). These alluvial outwash plains are fed by snowmelt fed tributaries of the Beas. Kuhls, varying from 1–25 km, divert streamflow through gravity channels constructed from locally available materials. The system supports a mixed-crop rotation of paddy, maize, wheat, and pulses, sustained by community managed water distribution. Kuhls are notable for their community managed resource model. Together these three components constitute the core Kangra Agricultural system.

2. Study Area: The Kangra Agricultural System

KAS extends across eight administrative blocks Baijnath, Palampur, Sullah, Nagrota Bagwan, Kangra, Dharamshala, Shahpur, and Bedumahadev of District Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, India. KAS spread is spatially equal to Rihlu Fan, Kangra fan and Palampur fan with an area of~435 km² (Srivastava et al., 2009). KAS is bounded by Dhauladhar mountain range (Lesser Himalaya) in north and Shivalik hills in south. KAS agricultural region is also corresponding to Kangra reentrant, which is the largest reentrant of Himalayan region, making it a geologically unique Landscape(Powers et al., 1998; Srivastava et al., 2009).

(Image 1: Pardeep Kumar (2025), reproduced from the author’s book “The Kangra Agricultural System: A GIAHS Perspective on Heritage and Resilience.)

3. Methodology

The study adopted the FAO’s Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) assessment framework, which evaluates agricultural heritage sites through five interrelated criteria:

- Landscape and seascape features.

- Food and livelihood security.

- Agro-biodiversity.

- Traditional knowledge systems.

- Cultural values and social organizations.

Each criterion was systematically analyzed to assess the eligibility of the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS) for potential GIAHS recognition. A mixed-method approach was used, combining spatial analysis, field investigation, and literature review.

3.1 Data Sources

Both primary and secondary data were utilized. Primary data included field observations of Kuhl irrigation channels, interviews with local farmers, Kuhl committee members, and artisans involved in maintenance and construction. Secondary data were obtained from government reports, Census of India (2011), geological and hydrological studies, and previous documentation on Himachal’s traditional irrigation systems and available GIAHS literature.

3.2 Spatial and Geomorphic Analysis

Topographic and slope analyses were carried out using SRTM 30m DEM data within QGIS 3.40.5 (Bratislava). Drainage and terrain features were extracted using hydrological and terrain processing tools. The mean slope, elevation range, and river terrace distribution were computed to assess the geomorphic suitability for gravity irrigation. Satellite imagery from Bhuvan LULC layers was used to delineate agricultural zones, forest cover, and settlement patterns.

3.3 Field Survey and Observations

Field surveys were conducted in selected Kuhl command areas across Palampur, Nagrota Bagwan, Shahpur, and Kangra blocks. Various Landscape features and cultural practices were noted down in the field.

3.4 Socio-economic and Cultural Assessment

Information on livelihood patterns, crop diversity, and gender roles was derived from Census 2011, News Papers and verified through local interviews. Cultural elements such as festivals, rituals, and food traditions linked to agriculture were documented through community participation and photographic records. Oral histories were also collected to trace continuity of traditional water rights and collective management practices.

3.5 Analytical Framework

Each criterion of the GIAHS framework was assessed using a qualitative–quantitative matrix, assigning indicative parameters to measure the extent of heritage value and sustainability.

- Landscape features were evaluated through geomorphic indicators and visual assessment of agricultural terraces.

- Food and livelihood security was analyzed using occupational and land-use data.

- Agro-biodiversity was assessed through field observations and species diversity in cropping systems.

- Traditional knowledge was documented via community narratives and historical irrigation records.

- Cultural and social organization was evaluated through rituals, institutions, and governance structures associated with Kuhl management.

3.6 Integration and Validation

Findings from field data, spatial analysis, and literature were integrated to develop a comprehensive evaluation of the KAS within the GIAHS framework. Validation was achieved through cross-verification with local administrative records and expert consultations with agricultural officers, geomorphologists, and anthropologists familiar with Kangra’s irrigation traditions.

4. Results and Discussion

a. Landscape features:

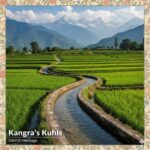

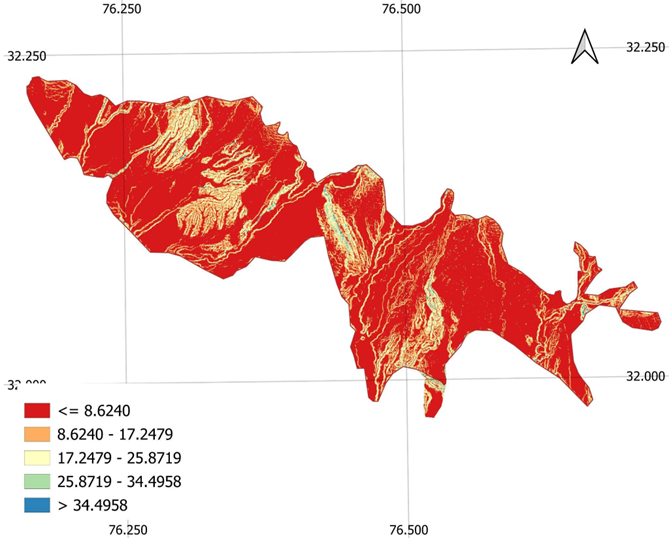

The Kangra Reentrant (31°45′N–32°15′N and 75°30′E–77°00′E) forms part of the Sub-Himalayan zone, where the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT) exhibits a broad curvature. It represents the largest inward bend of the Himalayan mountain front, stretching nearly 80 km across the Sub-Himalayan belt. The reentrant is shaped by a gently northward-tilting crust with slopes of about 2.5–3 degrees (Powers et al., 1998), forming a broad depositional basin at the foot of the Dhauladhar Range (Image 2). Descending rivers from Dhauladhar have deposited thick layers of sediments, creating extensive alluvial fans and fertile plains. Owing to its scale and morphology, Powers et al. (1998) referred to this feature as the “Kangra Paradox.”

(Image 2: The map shows local surface slope variation in the KAS region derived from SRTM DEM. Gentle slopes (≤8.6°) dominate the alluvial plains suitable for Kuhl irrigation and farming, while moderate to steep slopes (>17°) occur along the Dhauladhar foothills, used mainly for forests and tea plantations. The slope pattern reflects strong geomorphic control over land use and irrigation layout)

The long elevation profile along the 120.225 km transects between Adampur (240 m) and the Dhauladhar Range (3941 m) was extracted using the Profile Tool plugin in QGIS. The mean regional slope of 1.76° derived from this profile supports and quantitatively confirms the wedge-taper geometry of the Kangra Reentrant described by Powers et al., 1998.

(Image 3: The Long Profile slope between Adampur (240 ,31.43305655966964, 75.71803090201695) and the Dhauladhar (3941 m, 32.23465,76.68527) was calculated using a 30 m resolution Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) in QGIS 3.40.5 (Bratislava), projected to the Universal Transverse Mercator coordinate system (CRS: EPSG 32643 – WGS 84/UTM Zone 43N).

The KAS Landscape has a dense sub-parallel drainage pattern, which is very common to foreland basins. Major rivers such as Baner, Neugal, Gaj, and Manoni descend rapidly from the Dhauladhar, and join the Beas. Paror Anticline, near Nagrota Bagwan (Lower Shivalik) divides the Beas watershed in Kangra. The Multiple levels of river terraces are prominent across the river profile, reflecting cyclic phases of uplift, aggradation, and incision linked to Himalayan neotectonics and monsoon variation. These terraces provided the foundation for later agricultural fields and settlement.

The Kangra landscape evolved through four major stages: fan formation, fan dissection, terrace stabilization, and human adaptation. Its geomorphic evolution began nearly 11 million years ago, (Srivastava et al., 2009). Over the centuries local farmers converted these terraces into the agricultural field. Earliest evidence of Human-Landscape interaction dates back to 100 CE, a rare rock inscription in a Paddy field near Dharamshala mentions the existence of sacred grove in the region. The Kuhl irrigation system is a direct outcome of this Human-landscape co evolution. The migration of Girth people, which are the primary agriculture community of the region, might have accelerated the development of Terrace farm and Kuhls network. Preliminary genetic evidence shows the presence of Y-DNA haplogroup L1a2 (M357) in the Girth community(Syama et al., 2019), haplogroup L1a2 is linked with early agricultural expansion in South Asia , this suggests a deep regional continuity of farming populations. Further these geomorphic and human–landscape interactions resemble those observed in other mountain GIAHS landscapes such as the Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras (Centre, n.d.) and satisfy essential criteria of inclusion in GIAHS.

(Image 4: Kangra Fan – Paddy fields in September with the Dhauladhar mountain range in the background and monsoonal clouds hovering above, illustrating the fertile alluvial landscape sustained by seasonal rainfall.)

The region preserves extensive glacial deposits derived from the Dhauladhar granitoid. Moraines, transported by paleo-glaciers during the last ice age, occur across river terraces down to the base of the Siwalik. Glacier moraines are used by farmers in construction of Kuhls, water mills and other domestic usages. The moraine size ranges from large boulders to fine gravels and forms an integral part of the agricultural landscape. Paddy fields and tea gardens are interspersed with moraine deposits, representing a unique fusion of geological and cultural heritage (Kumar, 2025).

(Figure 5: Wah Tea Estate – Since 1857, A Legacy of Kangra Tea Cultivation Amidst Ice Age Moraines, Image Represent the rich Geological, Cultural and Agricultural Heritage of the region)

The regional landscape of KAS creates a strong orographic effect. In the months of June- July- August moisture laden monsoon winds strike the Dhauladhar front, resulting in high rainfall throughout the monsoon season, average rainfall of Kangra is 1751 MM. This dual influence of summer and winter monsoons supports continuous water availability in KAS region. The porous fan deposits enhance groundwater recharge through Kuhl percolation. In Monsoon

The Kangra landscape supports a remarkable climatic gradient from subtropical conditions in the southern Siwalik to temperate zones near the Dhauladhar. This diversity shapes cropping systems, settlement patterns, and vegetation distribution, reinforcing the adaptive complexity of the KAS. The upper slopes of the Dhauladhar are dominated by natural sal and Chir pine forests, while the lower slopes and terraces are characterized by a humanized agricultural mosaic of paddy fields, tea gardens, and orchards. The traditional land-use pattern also mirrors hydrological and topographic structure; villages occupy higher terraces, Kuhl channels follow contour lines, and fields spread across low terraces, forming a clear spatial harmony between land and water as mandated in GIAHS selection framework.

(Image 6: Glacier moraine, derived from Dhauladhar, spread across the paddy field is an integrated part of the Agricultural Landscape (Kumar, 2025))

b. Food and Livelihood Security

The Kangra Agricultural System (KAS) sustains a largely agrarian population within the Western Himalaya, around 94.3% of Kangra residents live in rural areas (Home | Government of India, n.d.) Agriculture remains the backbone of the local economy, with 44.9% of the workforce engaged in cultivation and a high proportion of smallholder farmers dependent on traditional irrigation through the Kuhl system. The limited urban population (5.7%) underscore the district’s rural character, while women constituted about 40% of the total workforce in Kangra District. Notably, 60% of cultivators were female, indicating the crucial role of women in sustaining traditional agricultural practices within the Kangra Agricultural System(Home | Government of India, n.d.)

Traditional barter systems such as Kao–Kalath continue to define economic relationships among the occupational groups, supporting the exchange of agricultural produce, tools, and daily necessities. The Gaddi pastoralists, through seasonal migration between the Dhauladhar highlands and the plains, maintain a symbiotic exchange of wool and livestock for grain, reinforcing agro-ecological interdependence. Tourism contributes an emerging livelihood dimension, with over 800,000 annual visitors (Year-2024) attracted to the region’s tea gardens, temples, monasteries, and natural landscapes, generating supplementary income through home stays, handicrafts, and local enterprises.

c. Agrobiodiversity

The Kangra Agricultural System (KAS) sustains rich agro-biodiversity encompassing diverse crops, livestock, and associated species that support ecological resilience and local livelihoods. Key cereals include wheat, rice, barley, and maize, alongside traditional millets such as bajra, kodra, and jowar. Oilseeds (sesame, mustard, fenugreek) and legumes (gram, pigeon pea) enhance soil fertility through nitrogen fixation, while vegetables and fruits add nutritional diversity. Indigenous livestock cattle, buffalo, goats, and poultry are adapted to the hilly terrain and integrated with crop systems. Surrounding forests contribute medicinal plants, herbs, and pollinators vital for ecosystem stability.

(Image 7: Rihlu Fan, Paddy Field in September Month)

Kangra Tea was introduced in the 19th century by Britishers and it got GI-tagged in 2005. It thrives on terraced slopes between Shivalik. Other allied practices such as lychee cultivation and scientific beekeeping since 1964 further enhance the region’s agro-ecosystem. These practices reflect the adaptive and sustainable foundations of KAS as a living heritage landscape

d. Traditional knowledge systems

Kangra agricultural system is based on Traditional Knowledge systems such as management of water resources, seed management, soil management, post-harvest management etc. Construction, maintenance and usage of Kuhls are based on century old traditional knowledge, inherited by villagers collectively from one generation to another generation. Kohli (The water man), is overall in charge of village Kuhls, his most important duty is to ensure people participation in Kuhls management and equal distribution of water among the villages and farmers. While the British era text Riwaj-I-Abpashi ,1874 defines the usage of Kuhls, practically it is collective knowledge of villagers which help to maintain the functioning of Kuhls. This Kind of community management is also found in historical Irrigation system at L’Horta de València, Spain L’Horta, n.d.)

Kuhls Engineering- Kuhls are built with precise longitudinal gradients to ensure optimal flow distribution across the river terrace. They carefully construct the Kuhl The diversion weirs are constructed from locally available stone and timber, and regulate stream discharge into contour-aligned main channels that minimize erosion. Flow velocity is balanced through controlled slopes and variable cross-sections to maintain hydraulic stability. Sediment management is achieved through oblique headworks and side sluices that facilitate selective silt removal. Routine community-led maintenance reinforces structural integrity, ensuring long-term operational efficiency and resilience within the agrarian hydrological framework.

(Image 8: Steel aqueduct carrying a Kuhl channel across a road near Palampur, Kangra. The structure represents the engineering adaptation of traditional irrigation systems (Kumar, 2025)

Terrace Farm- KAS Landscape represents different levels of river Terrace. These terraces have been skillfully converted into farm fields to optimize the use of Kuhl irrigation water. Fields are oriented at right angles to the fan slope, minimizing soil erosion and ensuring uniform water distribution across lower plots. This geomorphic and agricultural adaptation aligns closely with the FAO–GIAHS framework principles of sustainable land use and landscape harmony. Similar terrace-based systems can be seen in other recognized GIAHS sites such as the Rice Terraces of the Southern Mountainous and Hilly Areas, China, and the Ifugao Rice Terraces, Philippines, underscoring the global relevance of Kangra’s traditional terrace agriculture(Around the World | Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, n.d.).

Gharat: Gharat are water powered mills constructed on Kuhls. While Kuhls water power the Mills the Grinder of Kuhls are made locally available Dhauladhar Granite moraine. Although traditional Gharat has been replaced with modern electric mills, they are still essential for village economy.

(Image 9: The image shows terraced paddy fields at the base of the Dhauladhar Range, dotted with dome-shaped straw heaps locally known as Kuhada. These structures are built after the rice harvest for fodder preservation and soil protection during winter. The spatial arrangement of fields, settlements, and mountains in the background reflects the harmony between geomorphology and agriculture typical of the Kangra landscape. Such field-level practices demonstrate how traditional farming integrates resource efficiency, community labor, and climatic adaptation—core values of the FAO–GIAHS framework.)

Transhumance Tribe: The Gaddi, an indigenous pastoral community of the Kangra region, traditionally practice transhumance between the high-altitude pastures of the Dhauladhar Range and the fertile plains below. Their seasonal migration across steep mountain slopes and high passes exceeding 4,200 meters required deep environmental knowledge and adaptive herding skills. The continuity of this practice relies on the intergenerational transmission of such knowledge.

Other Traditional Knowledge: The Kural or Kuril folklore were once a method of monsoon intensity prediction, highlighting the early climatic understanding of people, though its practical use has declined with modern forecasting methods. Bamboo remains integral to the system, providing material for tools, containers, and storage structures. Post harvest management is marked by the construction of Kuhada (Image-9) dome-shaped straw heaps placed along terraced fields for efficient fodder preservation and land use during winter.

e. Cultural Value and Social Organizations

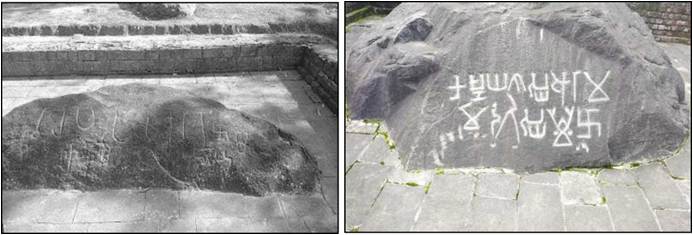

Early inscriptions, such as the 200 BCE Pathiyar Inscription near Nagrota Bagwan and the 100 CE Khaniyara Inscription near Dharamshala(Image-10)(Hāṇḍā, 1994), refers community ponds and sacred groves , which symbolize organized water management and ecological stewardship.

The 17th-century Kangra School of Painting, GI-tagged 2012, embodies this landscape through vivid depictions of local weather, terrain, and flora. Further the rituals and festivals such as Sair celebrate the harvest season, reinforcing agrarian spirituality through offerings of crops to local deities.

(Image 10: Left – Pathiyar Inscription, a rare bilingual record referencing an ancient community pond. Right – Khaniyara Inscription, mentioning the existence of a sacred grove in the region. Both inscriptions are engraved on glacial moraine blocks situated amid paddy fields and are protected by the Archaeological Survey of India.)

The worship of snake deities and the Rot offering at shrines express the region’s enduring agrarian faith. Folklore and folk songs centered on the Kuhls reveal emotional bonds between people and their environment. Culinary traditions such as Kangri Dham and crafts like earthen pottery further exemplify the integration of local agriculture, resource use, and cultural identity within the Kangra landscape. These cultural expressions illustrate the intimate linkage between water, landscape, and spirituality a defining feature of GIAHS landscapes worldwide.

5. Conclusion

The Kuhl irrigation-based Kangra Agricultural Systemwith exceptional Landscape demonstrates living heritage of water management, ecological adaptation, and community governance. Its inclusion in the GIAHS program would reinforce the global value of Himalayan agro-ecosystems and inspire contemporary models of participatory irrigation in fragile mountain environments.

Note :- © 2025 Pardeep Kumar. All rights reserved. Content from this article, including GIS maps and topographic profiles, may be cited with proper attribution to the author and the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17153175.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the insights shared by farmers and experts across Kangra District greatly enriched this research.

Reference:

Around the world | Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (n.d.). GIAHS. Retrieved October 15, 2025, from https://www.fao.org/giahs/around-the-world

Centre, U. W. H. (n.d.). Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved October 29, 2025, from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/722/

Hāṇḍā, O. (1994). Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, Upto 8th Century A.D. Indus Publishing Company.

Home | Government of India. (n.d.). Retrieved October 29, 2025, from https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/en

Kumar, P. (2025). The Kangra Agricultural System a GIAHS Perspective on Heritage and Resilience. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17153175

L'Horta de València| Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (n.d.). GIAHS. Retrieved October 29, 2025, from https://www.fao.org/giahs/giahs-around-the-world/spain-valencia-historical-irrigation-system/en

Powers, P., Lillie, R., & Yeats, R. (1998). Structure and shortening of the Kangra and Dehra Dun reentrants, Sub-Himalaya, India. Geological Society of America Bulletin – GEOL SOC AMER BULL, 110, 1010–1027. https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1998)110%253C1010:SASOTK%253E2.3.CO;2

Srivastava, P., Rajak, M. K., & Singh, L. P. (2009). Late Quaternary alluvial fans and paleosols of the Kangra basin, NW Himalaya: Tectonic and paleoclimatic implications. CATENA, 76, 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2008.10.004

Syama, A., Arun, V., Arunkumar, G., Subhadeepta, R., Friese, K., & Pitchappan, R. (2019). Origin and identity of the Brokpa of Dah-Hanu, Himalayas – an NRY-HG L1a2 (M357) legacy. Annals of Human Biology, 46, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460.2019.1694700