In the shadow of the snow-clad Dhauladhar mountains, the story of Kangra tea began nearly two centuries ago. What started as a quiet British experiment soon grew into one of India’s proudest agricultural legacies. Once admired in London and Amsterdam for its golden liquor and delicate flavour, Kangra tea today stands at a crossroads — struggling to survive in the very valley that once made it famous.

A Legacy Born in the 19th Century

Tea first came to Kangra around 1849, when Dr. Jameson, Superintendent of Botanical Gardens (North-West Provinces), identified the lower slopes of the Dhauladhar range as ideal for tea cultivation. He brought saplings from Almora and Dehradun and planted them in Kangra, Nagrota, and Bhawarna. The results were extraordinary.

Encouraged by this success, the British established the first commercial tea estate at Holta, near Palampur, in 1852, known as the Hailey Nagar Tea Estate. The mild Himalayan climate, heavy rainfall, and slightly acidic soil (pH ~5.4) proved perfect for the Camellia sinensis variety of tea, imported from China.

By the late 19th century, the Kangra Valley was producing some of the finest teas in the world. The Gazetteer of Kangra (1882–83) praised it as “superior to tea produced in any other part of India.” In 1886, Kangra tea won a Gold Medal at the London Exhibition, followed by global recognition in Amsterdam. Exports reached Central Asia, Kabul, Iran, and Europe, and Kangra tea became a symbol of Himalayan excellence.

The Golden Era and Sudden Decline

From the 1870s to the early 1900s, Kangra tea flourished. By the 1920s, the valley produced nearly half of India’s total green tea, employing thousands across Palampur, Baijnath, Dharamshala, and Jogindernagar. But disaster struck in 1905, when a massive earthquake destroyed plantations, factories, and lives. Many British planters abandoned their estates, selling them to local farmers.

Subsequent events — World War I, the Indo-Pak wars of 1965 and 1971, and the closure of trade routes through Pakistan and Afghanistan — further isolated the region’s tea market. Once a prized export, Kangra tea began to lose ground to newer tea regions in Assam and South India.

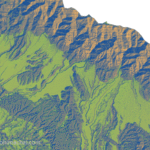

The Geography of Taste

Kangra tea grows between 900 and 1400 meters above sea level, across the southern slopes of the Dhauladhar range. The region receives 270–350 cm of rainfall annually, making it one of India’s wettest tea-growing zones. The soil, rich in organic matter and mildly acidic, gives Kangra tea its signature aroma and light golden liquor.

Unlike the bold Assam teas or the intensely floral Darjeeling, Kangra tea is known for its subtle flavour, smooth body, and natural sweetness — a combination that can only be produced under the unique Himalayan climate. The tea contains 13% catechins, strong natural antioxidants, along with 3% caffeine and amino acids such as theanine and glutamine, which lend a mild calming effect.

Production and People

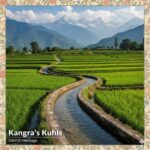

Today, around 3,600 small tea growers cultivate Kangra tea over about 2,300 hectares of land spread across six tehsils — Palampur, Baijnath, Dharamshala, Kangra, Jogindernagar, and Bhatiyat. Nearly 96% of growers own less than 2 hectares, making Kangra a smallholder-driven tea economy.

The Tea Board of India supports both black and green tea manufacturing. Traditional methods — withering, rolling, fermenting, and firing — are still followed, though modern factories have reduced withering time and improved energy efficiency. The major varieties include Pekoe, Pekoe Souchong, and Hyson, known for their fine appearance and bright brew.

The Decline and Struggle for Revival

At its peak, Kangra’s annual production reached 17–18 lakh kilograms. Today, it has fallen to 9–10 lakh kilograms. The area under cultivation has also shrunk to about 1,400 hectares. With the withdrawal of government subsidies in 2001 and the shelving of the revival master plan, many plantations turned unprofitable. Some have been converted into housing colonies, resorts, and tourist sites.

As profits fell and younger generations moved away, tea bushes aged, machinery rusted, and fields turned wild. The loss is not just economic — it is cultural. Kangra tea represents a living tradition of mountain agriculture, combining ecological adaptation with human craftsmanship.

What Makes It Unique

The Geographical Indication (GI) tag awarded to Kangra Tea protects it as a heritage product. Its uniqueness lies in:

- Distinct flavour and colour, known as the “Kangra flavour.”

- Low pest infestation and minimal pesticide use, making it naturally pure.

- High antioxidant content due to the cold Himalayan conditions.

- The deep-rooted cultural connection between tea, land, and community.

Scientific studies by CSIR-IHBT (Palampur) and UNIDO (2003) have confirmed that Kangra tea has among the highest EGCG content (a potent antioxidant) in India — higher even than Darjeeling cultivars in some samples.

The Way Forward

Reviving Kangra tea is not only about increasing production; it is about preserving a heritage landscape. The tea gardens stabilize slopes, conserve soil, and sustain local communities. Promoting organic certification, tea tourism, and branding under the GI label can help reconnect Kangra tea to national and international markets.

Kangra tea still holds its delicate aroma — faint yet unmistakable — reminding us that cultural heritage, once lost, cannot be recreated, only revived. The valley’s future depends on recognizing that this golden cup is more than a drink; it is a story steeped in history, nature, and resilience.