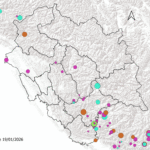

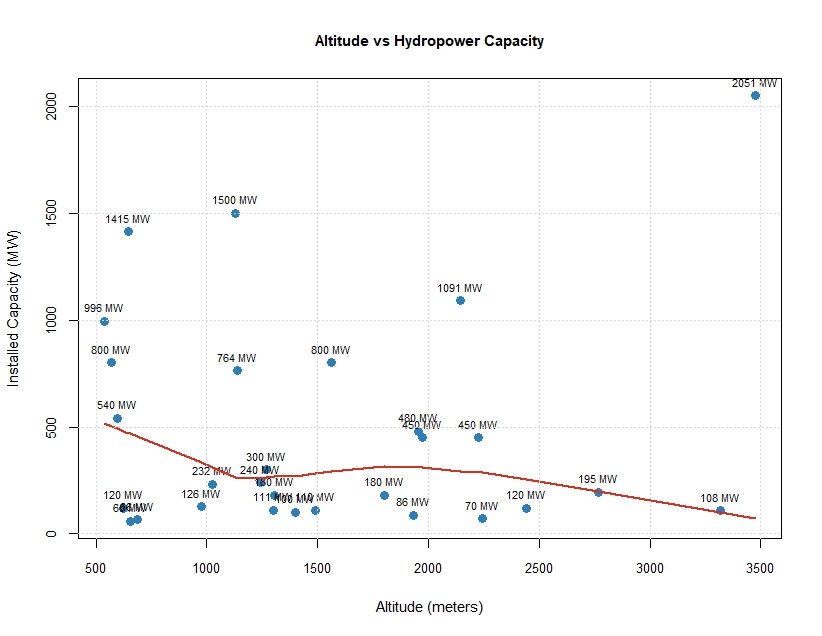

Altitude–capacity relationships in Himalayan hydropower systems are often assumed to be direct and deterministic, but the observed scatter plot of altitude versus installed hydropower capacity for projects in Himachal Pradesh clearly demonstrates that such an assumption is overly simplistic. .( More information about Hydro Project can be found here). You will understand why Lesser Himalaya is best place for extracting hydo Electricity.

Altitude Below 1000 Meter. ( Part of Lesser Himalaya and Shivalik )

At lower elevations, particularly below about 1,000 meters, the presence of several very large-capacity projects reflects the dominance of major trunk rivers such as the Sutlej and Beas. These rivers integrate vast upstream catchments, ensuring high and relatively stable discharge. The concentration of high-capacity points at low altitude therefore represents basin-scale control rather than any intrinsic advantage of low elevation itself. ( See More HP Geography )

Altitude Between 1000 and 2000 Mt ( Lesser Himalaya)

The mid-altitude zone, roughly between 1,000 and 2,000 meters, exhibits the greatest variability in installed capacity, ranging from small projects of under 100 MW to very large installations exceeding 1,000 MW. This wide dispersion at similar elevations highlights the decisive role of project design and river order. Within this altitudinal band, both trunk-river developments and tributary-based run-of-river schemes coexist. Projects tapping entire river systems through long diversion tunnels or cascade arrangements can achieve very high capacities, whereas nearby projects on smaller tributaries remain modest in scale..

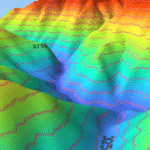

Altitude above 2000 Mtr ( Greater Himalaya and Trans Himalya)

At higher elevations, above approximately 2,000 meters, the general tendency is toward smaller project capacities, as reflected by the declining trend in the locally smoothed curve. High-altitude environments are characterized by narrower valleys, smaller and more seasonal catchments, greater sediment loads, and increased geological and construction risks. These factors limit reservoir size and favor run-of-river schemes that rely mainly on head rather than volume. Engineering challenge increase with increase in height.

Critical Insight Frow Study

The smoothed trend line in the plot should therefore be interpreted not as evidence of a causal decline in capacity with altitude, but as an expression of changing feasibility envelopes. As elevation increases, the average size of viable projects decreases, yet variability remains substantial due to differences in basin geometry, hydrological regime, and engineering strategy.

Overall, the graph captures a fundamental characteristic of Himalayan hydropower development in Himachal Pradesh: project capacity is governed by basin-scale hydrology and design choices, with altitude acting as a limiting boundary rather than a controlling variable. This pattern also carries important planning implications, suggesting that future hydropower expansion will increasingly involve higher-altitude, lower-capacity, and more numerous projects, with corresponding increases in environmental sensitivity and cumulative impacts per unit of energy generated.

Overall, sustainable hydropower development in Himachal Pradesh requires integrating hydrology, climate resilience, ecological limits, and economic feasibility, rather than relying solely on topographic advantage. This approach will ensure long-term energy security with reduced environmental and fiscal risk.

Thus Mantra for Planning of Hyrod Project Sanctioning and Feasibiltiy Study Capacity ∝ Discharge × Head.

Q: Does higher altitude always mean more hydropower capacity?

A: No. While higher altitudes provide more “Head,” our analysis shows that capacity actually peaks at mid-altitudes (1,000m-2,000m). This is because lower elevations often have much higher water discharge from major trunk rivers, which compensates for the lower vertical drop.

Q: Why is the Lesser Himalaya considered the best for hydro-electricity?

A: The Lesser Himalaya offers the perfect balance of $Discharge \times Head$. Unlike the Greater Himalaya, which has smaller, seasonal catchments and higher construction risks, the Lesser Himalaya features stable river systems and manageable topography for large-scale projects.

Q: What is the “Head” vs. “Discharge” relationship in Himachal?

A: Capacity is proportional to the product of Discharge and Head ($P \propto Q \times H$). At high altitudes, projects rely on “Head” (vertical drop). At lower altitudes, they rely on “Discharge” (volume of water). The most efficient projects integrate both factors.

Q: What are the main engineering challenges for high-altitude hydro projects?

A: Projects above 2,000 meters face increased geological risks, heavy sediment loads, and narrower valleys. These factors typically limit the size of reservoirs, favoring “Run-of-the-River” (RoR) schemes over large storage dams.

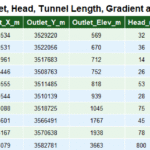

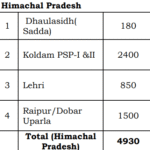

Note :- Following DATA was used, reader themseleves can reverify information with given Tools and Maths tools

Sr no Name

1 Bairaseul Power House

2 Bajoli hydel Project

3 Baspa 2 Hydel Project

4 Bhakhara Power Project

5 Chamea 3

6 Chamera 1

7 Chamera 2

8 Chhataru Hydel hydel Project

9 Daulasidh Hydro Project

10 Dehar Power Project

11 Giri Hydel Project

12 Greenko Hydro Project

13 Kashang Project

14 Kol Dam Power Project

15 Kuther Power Project

16 Larji Hydro Project

17 Luhri Hydro Project

18 Malana Power Project

19 Nathpa Jhakari hydel Project

20 Parbati Hydro Elctricity Project

21 Parbati Hydro Project II

22 Sainj Hydel Project

23 Sanjay Vidyut Pariyojna

24 Sewa II Power Project

25 Shanan Power Project

26 Shorang Hydro Project

27 Swara Kuddu Hydel Project

28 Thopan Powari Project

29 TRT Wangtu Hydro Project