A new climate trend of dry, snowless winters preceded by intense monsoon rainfall is altering the Himalayan landscape at an unprecedented scale. The Himalaya are facing a new kind of threat. For centuries, Himalayan landforms evolved under a balance of winter snow and summer monsoon. That balance is now breaking. Recent patterns of snowless winters and concentrated, high-intensity rainfall are reshaping the mountains rapidly.

How mountains react to snowless winters.

Over the past few decades, the Himalaya have received very little snowfall, confined to a short and irregular window. Earlier, large parts of the range remained snow-covered for most of the year. That condition no longer exists.The very meaning of names is changing. Dhauladhar, which literally implies a snowy white mountain range, no longer appears so. Today, these mountains look dark and exposed, marked by a parched stillness. A sense of ecological stress is visible simply by standing near the slopes. But the issue runs much deeper. The Himalaya are now facing another existential challenge: climate-controlled denudation. ( See more here )

What is happening.

Winters are snowless. Summers are mostly mild but interrupted by short bursts of extreme heat. Monsoons are intense and concentrated. This uneven climatic stress places multiple, conflicting pressures on Himalayan geology.

During winter, rocks remain dry and exposed. Cracks develop. Vegetation growth slows or disappears. The dry winter is followed by another dry summer, which widens fractures, loosens soil, and further weakens root binding. When intense monsoon rainfall arrives, the already fragile slopes fail. Rocks disintegrate, thin soils are washed away, rivers flood with sediment, and uprooted vegetation moves downstream. The landscape becomes young, unstable, and primed for the next erosion cycle.

Do we have visible proof.

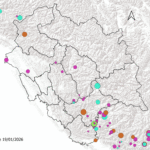

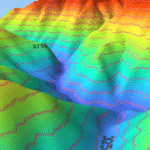

These changes are visible to the naked eye and can also be traced using Google Earth imagery. High Himalayan zones where snowfall was once regular are now repeatedly exposed to monsoonal moisture, slope failure, and surface disintegration. Landslides and rock breakdown are visible across many regions. Much attention remains focused on calculating glacier retreat, but that phase is already passing. The Himalaya are now entering a different and more complex stage of transformation. Unfortunately, this shift receives little attention. The changes are subtle, cumulative, and often escape both casual observation and satellite analysis.( See here evolution of Himalayan Landform)

During the 2025 monsoon, rain-shadow areas of the Dhauladhar in Bharmour region of Chamba district experienced severe landsliding. The regional ecology evolved for heavy snowfall and limited rainfall, not for intense monsoon precipitation. In Lahaul–Spiti, sparse vegetation and sudden monsoonal intrusion triggered destructive flash floods. Dhauladhar granatoid which is believe to be highly stable shows visible marks of of rocks disintegeration, these marks are visible from if you stand near Yol and look at rising hills.

In the Shivalik range, rainfall intensity has exceeded rock tolerance limits, making landslides increasingly common across the entire belt.What is unfolding is not a single disaster, but a slow restructuring of the Himalayan system itself.