The state government’s Sub-tropical Horticulture, Irrigation and Value Addition (SHIVA) project, funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), has become the launchpad for this transformation. With an investment of Rs 1,292 crore, the project aims to plant over one crore fruit saplings across the sub-tropical districts of Kangra, Sirmaur, Solan, Una, Bilaspur, Hamirpur, and Mandi.

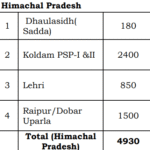

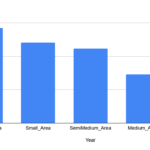

These regions, which sit between the temperate apple-growing belts and the warmer plains, offer just the right mix of moderate rainfall, mild winters, and fertile loamy soils for cultivating new crops. The SHIVA project will establish 400 fruit clusters over 6,000 hectares, supported by 162 irrigation schemes, of which 136 are already underway.

“We have conducted both market and crop suitability studies, and the results are encouraging,” said Devender Thakur, Project Director. “The ADB has approved the inclusion of avocado, dragon fruit, and blueberry in principle. Once formalities are complete, plantation will begin in selected clusters.” Adding India’s avocado wave.

Across India, the demand for avocados has exploded. In just five years, imports have risen from 234 tonnes in FY21 to nearly 20,000 tonnes in FY26, as the creamy fruit found its way into Indian kitchens. From Bengaluru’s breakfast cafés to Delhi’s health-conscious homes, avocados have evolved from a novelty to a lifestyle choice — packed with healthy fats, antioxidants, and premium appeal.

Farmers, too, are catching on. In Coorg, Punjab, and even Madhya Pradesh, small growers are investing heavily in avocado plantations. Gursimran Singh, a farmer from Malerkotla, Punjab, replaced lemons and guavas with 800 avocado saplings, betting on the fruit’s rising market. He expects a yield of 40 kg per tree and a price between ₹150–200 per kg, translating into ₹4 lakh per acre — double the income from conventional fruit crops.

Himachal’s mid-hills: A natural home for new fruits

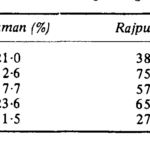

Himachal’s mid-hill regions — especially Kangra, Hamirpur, and lower Solan — could provide ideal conditions for these high-value crops. The temperature range of 15°C to 30°C, coupled with annual rainfall between 1,000 and 2,000 mm, supports avocado’s requirement for warmth without heat stress.

Varieties like Fuerte, Zutano, and India’s own Arka Coorg Ravi and Arka Coorg Supreme can withstand cooler nights and occasional frost, making them suitable for these altitudes. Farmers can also integrate them into mixed orchard systems alongside guava, citrus, or mango, ensuring both income stability and biodiversity.

Blueberries and dragon fruit, which thrive in slightly acidic soils and require regulated irrigation, are equally well-matched to the SHIVA project’s irrigation-supported clusters. With market prices exceeding ₹400 per kg, they could become profitable alternatives to apple and stone fruits in the coming decade.

Economic promise and ecological balance

Beyond profitability, the shift toward exotic crops aligns with Himachal’s goal of climate-resilient horticulture. Traditional apple belts are already shifting upward due to rising temperatures, while lower elevations face declining yields. Diversifying into avocado and similar fruits offers farmers an adaptive strategy that fits changing ecological realities.

The eco-friendly nature of these crops — requiring less pesticide and fewer cold-hours — could reduce chemical use and conserve soil health. Moreover, the introduction of value-addition units for avocado oil, dried blueberries, and dragon fruit juice could enhance local employment and export potential.

From apple revolution to avocado era

It has been nearly a century since Samuel Stokes introduced commercial apple farming to Himachal, changing its rural economy forever. Today, the SHIVA project’s new vision could spark a similar wave of transformation.

As the state prepares to nurture its first large-scale avocado orchards, the parallels are clear — new crops, new markets, and a new identity for Himachal’s farmers. From the lush terraces of Kangra to the subtropical valleys of Una, the idea of “green gold” is once again taking root — this time, in the creamy texture of an avocado and the bright pulp of a dragon fruit.