Introduction

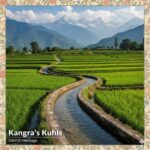

The Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) initiative, launched by the FAO in 2002, It recognizes globally significant agricultural systems that reflect the long-standing and harmonious interaction between humans and their landscapes, sustaining food security, biodiversity, and cultural heritage for centuries. As global agriculture shifts towards homogenization and industrialized monocultures, these heritage systems serve as models of agroecological balance, community resilience, and sustainable resource management. One such system is the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS) in Himachal Pradesh, India. Rooted in the Alluvial Fluvial/Outwash plains of the Dhauladhar range, KAS features the Kuhl irrigation system, an intricate, community-managed network of gravity-fed channels sourced from snow-fed rivers.

KAS coupled with terrace farming and a deep-seated socio-cultural fabric, exemplifies indigenous engineering, cooperative management, and environmental stewardship. Despite its ecological and socio-cultural importance, KAS remains largely unrecognized in global conservation frameworks.

This Book aims to assess the potential of KAS for inclusion in the GIAHS designation by comparing its agroecological, socio-cultural, and institutional attributes with similar globally recognized systems like Spain’s L’Horta de Valencia. FAO report titled: ‘Water management in the mountain: Kuhl irrigation already mentions and acknowledges the Kuhl irrigation of Himalaya’(1). The study further highlights the role of KAS in ensuring food and livelihood security, preserving agrobiodiversity, and maintaining cultural identity amid modern challenges.

Figure 1. Map Showing the location of L’ Horta and Kangra Agriculture System.

Chapter:1

World Wide GIAHS Site

To date, there are 89 designated GIAHS sites across 28 countries, spread across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe. These systems are vital for ensuring sustainable rural development, preserving agrobiodiversity, and promoting climate change adaptation and mitigation. However, while their ecological and socio-economic significance is widely acknowledged, the level of representation across different countries and regions varies substantially. The spatial distribution of GIAHS sites reveals a strong concentration in East Asia, the Mediterranean region, and Europe. In contrast, South Asia, which is home to 25 % of the world’s population, has only four designated sites. Given that agriculture has historically dominated the regional economy and the region has the highest Arable Land worldwide. The limited recognition of South Asian agricultural heritage can largely be attributed to a lack of dedicated research on GIAHS-related topics.

Table 1: List of countries with GIAHS sites.

| Name of Country | Number of Sites | Name of Country | Number of Sites | Name of Country | Number of Sites |

| Algeria | 1 | Indonesia | 1 | Republic of Korea | 7 |

| Andorra | 1 | Iran | 6 | Sao Tome and Principe. | 1 |

| Austria | 2 | Italy | 2 | Spain | 5 |

| Bangladesh | 1 | Japan | 15 | Sri Lanka | 1 |

| Brazil | 1 | Kenya | 1 | Tanzania | 2 |

| Chile | 1 | Mexico | 2 | Thailand | 1 |

| China | 22 | Morocco | 3 | Tunisia | 3 |

| Ecuador | 2 | Peru | 1 | United Arab Emirates | 1 |

| Egypt | 1 | Philippines | 1 | Grand Total | 89 |

| India | 3 | Portugal | 1 |

The Thematic Classification of GIAHS sites outlines seven key types of traditional agricultural systems .These include rice-based systems found widely across Asia, such as terraced and wetland rice cultivation in China, the Philippines, and Japan, often integrated with fish farming. Perennial crop and plantation systems revolve around long-lived crops like tea in China and Sri Lanka, wasabi in Japan, and cocoa or coffee agroforestry in Latin America. Water and irrigation systems highlight ancient techniques such as the Canal Bases system of Spain, Iran’s qanats, and underground networks like Aflaj and Karez. Nomadic pastoral systems, seen in Mongolia, Iran, and Kenya, reflect mobile livestock practices adapted to changing climates. Agroforestry and mixed farming systems support biodiversity through indigenous methods, as seen in the Amazon .Fishing and coastal systems, like those in Korea, Chile, and Bangladesh, represent sustainable marine and estuarine resource use. Together, these themes reflect the resilience, cultural continuity, and ecological wisdom embedded in GIAHS landscapes.

Chapter -2

Kangra Agriculture System

The Kangra Agricultural System site is located in the Western Himalayas in northern India. These sites lie within the Kangra District of the state of Himachal Pradesh. The region spans across several administrative blocks including Baijnath, Palampur, Panchrukhi, Bhawarna, Bhedu Mahadev, Nagrota Bagwan, Kangra, Dharamshala, and Rait. The majority of these blocks are predominantly rural in character.

Key components of Kangra Agriculture System are Vast Fluvial/Outwash Plains, Network of Kuhls and Community management. The Kangra Plain is one of the largest fans in the Himalayas, formed during the Quaternary glaciations by sediments deposited from glacial melt and high-energy rivers descending from the Dhauladhar Range—which mean “snow-covered” mountains. These plains lie at elevations ranging from approximately 800 to 1200 meters above sea level, sloping southward into the Sub-Himalayan foothills.

Over centuries, local communities particularly people of Ghirt Castes have converted these glacio-fluvial plains into stepped terrace farms, optimized for water retention and soil stability. The Western Disturbances bring snow to the higher reaches, while the Southwest Indian Monsoon delivers high-intensity rainfall, making the region one of rich water availability and dense stream networks. During the monsoon, large sections of these terrace farms become seasonal wetlands, supporting paddy cultivation and temporary aquaculture.

The interaction between humans and this outwash terrain has shaped a distinct Agro-cultural landscape, drawing thousands of tourists annually. The plains feature a mosaic of rice paddies, tea gardens, temples, village ponds, and rivers. One rare inscription from Khanyara village Near Dharamshala (circa 100 CE) mentions a community garden (vatika), providing historical continuity to the agroecological traditions of the region. Another inscription (circa 200 BCE) located in Paddy field , Pathiyar Nagrota Bagwan mentions the existence of community Pond.

The Kuhl System is the defining feature of Kangra irrigation infrastructure. Kuhls are gravity-fed, human-engineered water channels that divert glacial and stream water from the Dhauladhar streams onto the outwash plains. These channels are often kilometers long, skillfully engineered to follow natural river terraces and designed to descend gradually, ensuring maximum coverage of agricultural fields.Kuhls begin at a diversion structure—traditionally made of stone, brushwood, or more recently, concrete—called a danga, constructed in the riverbed. Water is then channeled across the terraces and finally returned to the river system downstream. This closed-loop system ensures both irrigation and water conservation.

What makes Kuhls truly unique is their community governance model. Historically, the construction, maintenance, and water distribution of kuhls have been overseen by local agricultural communities through customary rules and the appointment of a Kohli (water man). The Kohli oversees daily operation, schedules irrigation turns, resolves disputes, and organizes annual Kuhls rituals. The Riwaj-i-Abpashi (Customs of Irrigation) is a colonial-era codification of traditional water rights, irrigation customs, and responsibilities associated with Kuhl irrigation systems .This system has been a resilient form of common property resource management, deeply embedded in the local socio-legal traditions of Kangra. Though similar irrigation practices exist elsewhere in the Himalayas, the scale, density, and communal governance structure of the Kangra Kuhls are unparalleled.

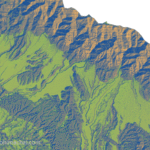

Figure 2: Showing Kangra Agriculture System enclosed by Dhauladhar Mountain range in north, Shivalik Mountain range in south. Figure Also shows State and District Boundary.

“The Kangra Agricultural Sites are located in the Western Himalayas in northern India. These sites lie within the Kangra District of the state of Himachal Pradesh. The region spans across several administrative blocks including Baijnath, Palampur, Panchrukhi, Bhawarna, Bhedu Mahadev, Nagrota Bagwan, Kangra, Dharamshala, and Rait. The majority of these blocks are predominantly rural in character.Several rivers such as Binwa, Banganga, Bander, Mununi, and Manjhi flow through this area. The district, as a whole—with a few exceptions—falls within the catchment of the Beas River, a major tributary of the Sutlej River. The Sutlej itself is a tributary of the Indus River, which ultimately drains into the Arabian Sea in the Indian Ocean.”

Administrative Division

Country: India

└── State: Himachal Pradesh

└── District: Kangra

└── Blocks: Baijnath, Palampur, Panchrukhi, Bhawarna, Bhedu Mahadev, Nagrota Bagwan, Kangra, Dharamshala, Rait

Chapter-3

L’Horta de València

L’Horta de València, located on the Mediterranean coast of eastern Spain, is one of Europe’s most iconic traditional agricultural landscapes. It encompasses a vast peri-urban agrarian zone that stretches across the plains surrounding the city of Valencia, nourished by the Turia River and fed by an elaborate system of community-managed irrigation channels. This system has supported a continuous agricultural tradition for more than a thousand years and is globally recognized for its historical depth, cultural richness, and hydraulic engineering excellence.

Rooted in Islamic hydraulic knowledge from the 8th to 13th centuries and later refined through local adaptations, L’Horta operates on a gravity-fed irrigation network known as the Acequia system. This decentralized but well-coordinated infrastructure consists of mother canals (acequias madres), secondary and tertiary distribution channels, and field-level furrows, which altogether ensure equitable water distribution. The water is allocated and managed by user communities (Comunidades de Regantes) following oral traditions and written codes that have evolved over centuries, including the famous Tribunal de las Aguas, a UNESCO-recognized water court that resolves irrigation disputes in real time.

Figure 3:Map of L’Horta de Valencia

The GIAHS site of L’Horta de València is situated in the eastern coastal province of Valencia, within the Autonomous Community of Valencia, Spain. Administratively, it spans across the three comarcal districts of Horta Nord, Horta Oest, and Horta Sud, as well as the Municipality of València. The GIAHS territory encompasses approximately 17 km² of non-urban land, distributed among 35 actively contributing municipalities out of a total of 45 that fall within the traditional irrigated landscape known as ‘l’Horta.’ These municipalities collectively represent the historical agricultural system based on the Turia River irrigation network, including the Acequia Real de Moncada and communities governed by the Tribunal de las Aguas.”

Administrative Division

Spain

└── Autonomous Community: Valencia

└── Province: València

└── Comarcas (e.g., Horta Nord, Sud, Oest)

└── Municipalities (e.g., Alboraya, Mislata, Torrent)

The landscape of L’Horta features small, intensively cultivated plots, primarily producing vegetables, fruits, and citrus—many for local markets. Its pattern of mosaic-like fields, agricultural paths, historic farmhouses (alquerías), and urban-rural integration exemplifies an enduring human-nature relationship. Despite urban pressures, L’Horta has preserved both its productive vitality and social fabric, making it a living repository of agroecological knowledge, cultural identity, and sustainable land use.

Today, L’Horta stands as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) due to its fusion of historical irrigation engineering, community-based governance, and adaptive, low-input agriculture. It represents a model for sustainable peri-urban farming under climate and urbanization pressures, offering valuable insights into how traditional knowledge can co-evolve with modern challenges.

Chapter-4

Geography and Landscape.

The Kangra Agricultural System (KAS) is located in the mid-altitudinal zone of the western Himalayan foothills, within the elevation range of 500–1500 meters above sea level. Geographically, the system is bounded to the north by the Dhauladhar range of the Lesser Himalaya (peaking at ~4200 meters) and to the south by the Shivalik hills (~1200 meters). The central part of the proposed site comprises extensive outwash plains, primarily developed through Pleistocene Glacial and fluvial activity. These plains have been categorized into three major depositional systems—namely the Rihlu Fan, Kangra Fan, and Palampur Fan deposited by high-energy streams and meltwater events (Srivastava, Rajak, & Singh, 2013, p. 138).

Originally characterized by steep gradients, erratic boulders, poorly sorted sediments, and unstable drainage, these fan surfaces were not immediately suitable for intensive agriculture. The transformation of these alluvial fans into stable, terraced agricultural zones was a result of prolonged and coordinated human intervention. Communities employed traditional engineering practices to reshape the terrain, including boulder clearance, surface leveling, and the construction of stone-reinforced terrace bunds. The integration of the gravity-based kuhl irrigation network further enabled controlled water distribution, transforming the geomorphic units into viable agro-ecological zones.

Figure 4: Showing the Broader Fan of Kangra Agriculture System.

The timeline of the formation of Dhauladhar Outwash Plains ((Srivastava, Rajak, & Singh, 2013).)

- ~50 Myr ago: Formation of the Himalayan mountain range due to the collision of the Indian plate with the Eurasian plate.

- 11 Ma: Sedimentation in the Kangra basin began.

- 200 ka: Cessation of Upper Siwalik sedimentation.

- 100 ka: Late Quaternary fan building activity began.

- 78 ka: Formation of loess in proximal settings of the alluvial fans.

- 44 ka: Formation of loess in proximal settings continued.

- 30 ka: Formation of loess in distal settings of the alluvial fans.

- 20 ka: Formation of loess in distal settings continued.

- 75-65 ka and 50-35 ka: Reactivation of the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT).

- 19.9 ka to present: Deposition over the younger surfaces in the Kangra basin continued with intervening breaks and formation of paleosols.

The L’Horta de València agro-landscape evolved from a dynamic coastal plain characterized by seasonal marshes, fluvial channels, and alluvial sediments deposited by the Turia River. Originally composed of hydromorphic soils with high salinity and poor drainage, this environment was unsuitable for sustained agriculture without substantial human intervention. Over centuries, the landscape underwent a fundamental transformation driven by engineered water control and land reclamation strategies.

The earliest known modifications can be attributed to Roman hydraulic engineering, which introduced primary irrigation channels. However, it was during the Islamic period (8th–13th century CE) that systematic landscape-scale transformation took place. A highly sophisticated gravity-fed irrigation network—based on diversion from the Turia River—was established, including a network of acequias (irrigation canals), azuds (weirs), and partidores (water distributors). These structures allowed for the redistribution of river water to otherwise poorly drained and saline soils, enabling year-round cultivation.

Through these interventions, the natural coastal hydrology was reorganized into a spatially ordered agricultural matrix. The original wetland areas were systematically drained and parcelled into rectangular plots (huertas), creating a mosaic landscape that maximized water efficiency and microclimatic advantages. Crucially, these landscape transformations were supported by robust socio-legal institutions, including the Tribunal de las Aguas, a customary court governing irrigation rights and water-sharing norms since the 10th century.

Table 2: KAS and L’Horta de València

| Sr. No. | Key Point | Kangra Agricultural System (KAS) | L’Horta de València (HoV) |

| 1 | Terrain and Landform | Alluvial-glacial outwash fans (Rihlu, Kangra, Palampur Fans); steep slopes and coarse sediments transformed into terraced fields | Coastal alluvial plain formed by the Turia River; flat, reclaimed marshy land |

| 2 | Geomorphic Transformation | Manual leveling of slopes, terracing to create agricultural plots, integration of gravity-fed kuhls for water management | Reclamation of saline soils through hydraulic engineering, construction of acequias and azuds for irrigation |

| 3 | Landscape Configuration | Mosaic of terraced farms, forests, rivers, and settlements on slopes | Coastal agricultural mosaic with canals, gardens, and interstitial spaces within the urban matrix |

| 4 | Water Management & Irrigation Infrastructure | Dense network of streams and kuhls with decentralized management | Large-scale, organized canal systems (acequias) with formalized water rights management |

| 5 | Urban Interface | Low urban encroachment, peri-rural landscape with minimal urbanization pressure | High peri-urban pressure, fragmented farming amidst urban sprawl |

| 6 | Rainfall | The steep rise of Dhauladhar causes the wind to cool rapidly and produce frequent adiabatic rainfall. Which further ensures the availability of water. | Sea winds bring moisture and produce rainfall. |

Chapter-4.1

Water Management and Irrigation Engineering

Irrigation lies at the heart of both systems, but their hydraulic logic differs due to landscape. KAS uses an indigenous Kuhl irrigation system, which diverts glacial or stream water through manually dug channels that flow downslope. These are open, unlined, and require annual maintenance due to destruction and silting. The whole region has a very dense network of rivers. Conversely, L’Horta’s acequia network is a system of lined canals originating from the Turia River, distributed through gravity but with advanced engineering, including regulation gates and overflow structures. Both systems ensure equitable water access but reflect topography-driven adaptation: mountainous gravity-fed flow in Kangra vs lowland-controlled flow in València.

Kuhl covered a vast area of around 356 km2, out of which 336.108 Sq Km is Agriculture Land which is irrigated by Kuhls ,in comparison L’Horta’s covered only 18 Km sq area of irrigation. Instead of a vast network of Canal , KAS irrigation infrastructure lies on a small Kuhl. The longest of these Kuhl is around 25 Km. According to the 1918 “Riwaj-I-Abpashi” (Book of Irrigation Customs), the Kangra Valley had approximately 715 major kuhls and over 2,500 minor kuhls, collectively irrigating about 30,000 hectares of farmland. However, this statistics has changed significantly due to government intervention.

Table 3: Comparison of Irrigation Regime

| Parameter | Kuhls of Kangra | Acequias of L’Horta (València) |

| River | Large Number of Kuhls, Awa, Neugal, Binwa , Bander, Manuni, Gajj etc | Turia river and Jucar river |

| Area irrigated | 336 Sq Km | 17 Sq. Km.( Core Historical Area) |

| Average Length of kuhls | 15-20 Km | 15-20 Km. |

| Governing Institution | Inter and Intra village-level kuhl committees and Panchayats. Thus Kuhls are mostly community Driven institutions. | Legally recognized Water User Associations (WUAs); regulated by Tribunal de las Aguas |

| Legal Status | Mostly customary and oral traditions, Riwaj-i-Abpashi (1868), The Himachal Pradesh Minor Canals Act, 1976 . | Institutionalized by law; EU-recognized frameworks |

| Conflict Resolution | Resolved locally by elders or water managers (kohlis); consensus-based. | Tribunal de las Aguas; decisions are binding and swift |

| Water Distribution System | Rotational and demand-based allocation; monitored by kohlis. | Pre-defined turns, fixed schedules based on centuries-old rights and land ownership |

| Maintenance Responsibility | Maintenance is Community-driven and is voluntary in nature, Kuhls are annually repaired before irrigation. The government also provides funds to repair Kuhl. | It is Obligatory for members of WUAs to participate, Annual feed is paid for maintenance |

| Knowledge Transmission | Oral traditions, passed through generations within households. | Written rules, ledgers, Oral practices |

| Institutional Flexibility | Highly adaptive, responds to local climate, landslides, stream shifts. | Stable but codified, with capacity to absorb innovations via community-science collaboration |

| Key Governance Figures | Kuhlis (watermen), Kuhl Committee and Revenue Department. | Sindics (water judges); elected farmers; water guards employed by the WUA. |

| Scale of Operation | Typically 1–3 villages per kuhl, serving a few hundred hectares. | Large-scale for example Acequia de Moncada serves 5,200 ha and 10,000 Plus users. |

Table 4: Difference Between Irrigation Technology

| Parameter | Kuhl System (Kangra, India) | Acequia System (L’Horta, Spain) |

| Water Source | Mountain streams, tributaries of the Beas (e.g., Neugal, Binwa) | Turia River (main); Júcar River (supplementary in south) |

| Intake Structure | Temporary lateral barrier (Danga) made of stones/logs; built seasonally | Permanent weirs (Assuts) with stone masonry and sluice gates |

| Canal Material | Main kuhls partly concrete-lined; others are earthen | Main acequias mostly unlined or stone-lined; some modern sections use concrete |

| Canal Size | Small to medium channels (~0.5 to 2 m wide); adapted to steep, terraced terrain | Large mother canals (up to 6–7 meters wide); built along gentle contours |

| Distribution Hierarchy | Main Kuhl → Secondary Kuhl → Field Channels | Mother Acequia → Arms (brazos) → Filas & Regadoras (small rows/channels) |

| Flow Diversion Points | Tap: traditional branching point; managed manually | Partidor: permanent splitter; Llengües direct flow; precise turn-based control |

| Water Regulation Tools | Earth grass seals (Cheb) at taps; flow diverted manually with spades or bunds | Wooden/metal gates (postes) in galzes (grooves); operated with paletas to control flow |

| Irrigation Method | Mostly flood irrigation with basic field division; minor bunding | Full surface flooding; precise division into basins (caballones) for water control |

| Maintenance & Flexibility | High flexibility; realigned after floods or landslides; community-managed | Stable but rigid; fixed layout; maintenance by WUAs; limited flexibility |

Figure 5: Left Hand Side Image shows Kuhls of Kangra Valley and Right hand image shows irrigation canal of L’Horta.

Chapter-4.2

Historical Evolution and Institutional Frameworks

The word Kuhl is made of two words “Ku + Uhl”. The Suffix ‘Ku’’ is from unknown lost language, whereas the root word ‘Uhl’ , suggests Dravidian origin and points toward a kind of a river channel. The existence of other rivers with the root word ‘ ‘Uhl’’ in the Himalaya prove the point. However historical mentions of the Kuhl system dating back to the Medieval India and British colonial surveys thus KAS has thrived for over 500 years. The vast majority of Kuhls are constructed by local Grith (also pronounced as Girath) farmers with exception to large Kuhls which were state sponsored. In fact development and maintenance of such a vast Kuhl network was not possible until Girt people began to migrate to valleys and start shaping the regional landscape.

L’Horta’s evolution dates back to the Roman era, with significant enhancements during the Islamic period in the 10th century. Its most notable institutional feature is the Tribunal de las Aguas, a 1,000-year-old water court that continues to resolve irrigation disputes in public using oral proceedings, a remarkable example of enduring participatory governance.

Table 5: Origin of the Major Kuhls in Tehsils Kangra and Palampur

| Constructed By | Kangra Tehsil | Palampur Tehsil | Total | % of Total |

| Collectivity of Landholders | 332 | 217 | 549 | 77.00% |

| Individual | 66 | 37 | 103 | 14.40% |

| Raja/Rani (State-Sponsored) | 5 | 14 | 19 | 2.70% |

| British Government | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.30% |

| Not Known | 5 | 35 | 40 | 5.60% |

| Total | 409 | 304 | 713 | 100% |

Sources: Riwaj-i-Abpashi (1919).

*Hutchison, J., & Vogel, J. P. (1933). History of the Punjab Hill States. Government Press, Lahore.

*Charak, S. R. (1979). History and Culture of Himalayan States, Volume III. Light & Life Publishers.

As cited in Baker, Judy M. (2005). Communities, Networks, and the State, p. 96.

Table 6: Origin Dates and Characteristics of Nine State-Sponsored Kuhls in the Neugal Basin

| Kuhl Name | When Constructed | % of Tikas Irrigated | Command Area (ha) | Length (km) |

| Dewan Chand Kuhl | 1690–1697 | 24 | 185 | 25 |

| Kirpal Chand Kuhl | 1690–1697 | 62 | 1713 | 33 |

| Raniya Kuhl | 1759–1774 | 10 | 545 | 12 |

| Rai Kuhl | 1775 | 28 | 820 | 20 |

| Giaruhl Kuhl | 1760–1785 | — | — | — |

| Dadhuhl Kuhl | 1775–1805 | — | ~ | — |

| Dai Kuhl | 1775–1805 | 22 | 357 | 25 |

| Dei Kuhl | 1775–1805 | — | — | — |

| Mian Fateh Chand Kuhl | 1775–1805 | 23 | 256 | 20 |

| Sangar Chand Kuhl | 1775–1805 | 16 | 324 | 26 |

Sources:Riwaj-i-Abpashi (1919)

* Hutchison, J., & Vogel, J. P. (1933). History of the Punjab Hill States. Government Press, Lahore.

*Charak, S. R. (1979). History and Culture of Himalayan States, Volume III. Light & Life Publishers.

*As cited in Baker, Judy M. (2005). Communities, Networks, and the State, p. 96.

Chapter -4. 2

Land Cover and Land Utilisation

This section presents a comparative analysis of land use and land cover (LULC) patterns in the proposed GIAHS site of the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS), Himachal Pradesh, India, and the established GIAHS site of L’Horta de València, Spain. The analysis utilizes the European Space Agency’s World Cover 10m 2021 v200 dataset, which classifies global land cover using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 imagery (ESA, 2023).

( Figure 6: LULC Map Left Hand side- KAS and Right Hand side: L’ Horta de Valencia)

Table 7: Comparison of LULC in KAS and L’ Horta de Valencia.

| Land Cover Class | L’Horta de València (%) | Kangra Agricultural System (%) |

| Tree Cover | 10–15 | 60–65 |

| Cropland | 30–35 | 20–25 |

| Built-up | 25–30 | 8–10 |

| Grassland | 10 | 5–8 |

| Shrubland | 10 | 2–3 |

| Water Bodies | 3–5 | ~1 |

| Herbaceous Wetland | 2–3 | Absent |

| Bare/Sparse Vegetation | 2 | 1–2 |

Analysis of Key Land Cover Components

Tree Cover :In KAS, tree cover is the dominant LULC class, forming a dense matrix around croplands and settlements. This reflects the integration of agroforestry and natural forests, and underscores ecological sustainability and biodiversity potential. In contrast, tree cover in L’Horta is limited to green belts or isolated clusters, as the majority of the landscape is cultivated or urbanized.

Croplands :L’Horta features spatially uniform and geometrically organized croplands with high irrigation intensity, supported by the acequia system. Croplands occupy over one-third of the region, though increasingly fragmented by urban growth. In KAS, croplands are typically terraced and follow elevation contours, with clear dependence on gravity-fed Kuhls. The smaller coverage reflects both topographic constraints and forest interspersion.

Built-up Areas: L’Horta exhibits a high degree of urban encroachment, especially along the western and southern edges adjoining València city. Urban infrastructure penetrates deep into agricultural zones, increasing landscape fragmentation. In KAS, built-up areas are sparse, mostly confined to small villages and scattered roadside settlements, resulting in low edge density and minimal fragmentation. Water Bodies and

Wetlands: L’Horta’s landscape includes visible standing water bodies, most notably the Albufera Lake and associated wetlands. These support irrigation as well as ecological services. KAS lacks significant standing water features; instead, its irrigation relies on perennial streams and manually constructed Kuhls. Herbaceous wetlands are absent in KAS, consistent with its hilly, forested terrain.

Shrubland and Grassland: Shrubland and grassland are more prominent in KAS, serving as buffers between forest and cropland, or as degraded/fallow areas. In L’Horta, these classes are marginal, possibly representing temporary fallows or roadside vegetation.

Landscape Integrity and Fragmentation: The spatial configuration of LULC classes reveals important ecological insights. L’Horta is characterized by high edge density and patch fragmentation, primarily due to urban sprawl and road infrastructure. This increases vulnerability to land-use conflicts and biodiversity loss. In contrast, KAS maintains a cohesive land cover structure with extensive contiguous tree cover and low built-up density, supporting landscape connectivity and resilience.

Urbanization Trends and Ecological Pressure:The red-coded built-up zones in L’Horta clearly indicate intense urban growth between 2016 and 2021, which has rapidly replaced agricultural land. This poses significant risks to the integrity of its historic irrigation system and associated croplands. KAS is at an earlier stage of this trajectory, with initial expansion observed around urban centers such as Dharamshala and Kangra. However, the current spatial patterns suggest relatively balanced rural-urban interactions.

Further Analysis of LULC Cover in the KAS Site

To maintain consistency in land use and land cover (LULC) comparisons between the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS) and L’Horta de Valencia, the analysis initially utilized the European Space Agency’s WorldCover 10m 2021 v200 dataset, which classifies global land cover using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 satellite imagery (ESA, 2023). While this dataset offers standardized global coverage, it presents limitations in accurately reflecting the LULC characteristics of the KAS site. Specifically, due to the small, fragmented nature of farmland parcels in Kangra—unlike the larger and more contiguous plots found in L’Horta—there is a tendency for agricultural land to be misclassified as wasteland, grassland, or tree cover in the ESA dataset. These misclassifications result in an underestimation of cultivated land in the region.

To correct this discrepancy and provide a more regionally accurate depiction, this study supplements the global dataset with data from the Bhuvan Geoportal (National Remote Sensing Centre, ISRO), utilizing the SISDP Phase-2 LULC dataset for Himachal Pradesh (2016–2019). This dataset offers higher spatial resolution and classification detail suitable for capturing the complex agricultural mosaic of the Site.

Table-8 LULC cover KAS site

| Particular | Area |

| Agriculture | 336.108 |

| Built-up | 76.552 |

| Forest | 75.452 |

| Grasslands / Grazing Lands | 12.939 |

| Others | 0.064 |

| Water Bodies | 9.12 |

| Grand Total (Area in Sq.Km) | 510.235 |

(Figure 7: LULC map of KAS for further Analysis)

(Total Agriculture Land 336.108 Sq. Km). The LULC classification used in this study was obtained from the Bhuvan Geoportal (NRSC, ISRO), specifically the SISDP Phase-2 LULC 10K data for Himachal Pradesh (2016–2019). In fragmented agro-ecological zones such as the Kangra Valley, parcels classified as “wastelands” often support intermittent or seasonal cultivation. Therefore, to more accurately reflect agricultural extent, Agricultural Land and Wastelands classes were merged, as done in similar mountainous land-use studies (Sharma et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2019).

Chapter-5

Agrobiodiversity and Culture

KAS supports subsistence agriculture with multi-seasonal, low-input farming. Dominant crops include rice, maize, wheat, mustard, pulses, vegetables etc cultivated in rotation across terraced fields. Agrobiodiversity is preserved through traditional seed saving and intercropping. Further a study conducted in the Kangra area by Katoch et al. (2017) documented the use of 130 medicinal plant species, belonging to 105 genera and 53 families, with 25–30 species commonly used by the local tribal communities for treating a range of ailments. These plants are integral to the traditional healthcare system in the region, with applications from simple headaches to more severe conditions like high fever (Katoch et al., 2017). In addition to medicinal uses, some of these plants are sources of colorants and tannins, with 13 plant species identified as providers of these materials (Katoch et al., 2017). (Katoch, Mittu & Bhat, Arbeen & Malladi, Satyanarayana Murthy. (2017). To Study the Ethnobotany and Angiosperm Diversity of Kangra District (H.P.). )

L’Horta’s cropping is commercial and market-oriented, emphasizing horticulture such as oranges, tomatoes, lettuce, and artichokes. The flat terrain and year-round irrigation enable intensive cultivation and higher productivity. Despite their different market orientations, both systems rely on diversified cropping suited to local climate and water availability. Soil conservation in KAS is managed through contour bunding, terrace wall maintenance, composting, and mulching—practices that reduce erosion and retain moisture. The loamy soils vary across elevation zones and are nurtured with organic inputs. In L’Horta, centuries of manuring and green composting on fertile alluvial soils have sustained productivity. Its irrigation system helps maintain soil moisture uniformly across fields, minimizing salinization. While one system manages sloped terrain and rainwater, the other maximizes the productivity of flat, irrigated soils—both demonstrating sustainable land-use ethics.

Cultural Practices and Societal Structures :KAS is deeply interwoven with socio-cultural traditions, with Agricultural festivals like Sair, Agricultural rituals like worship of Kuhl and village deity, and community labor defining rural life and caste hierarchy. The Kuhl is not merely an irrigation channel but a symbol of cooperation and shared heritage. Similarly, in L’Horta, the acequias shape cultural identity through festivals, local markets, and the legacy of the Tribunal de las Aguas. These cultural elements reinforce the notion that agricultural systems are not just technical landscapes, but also living cultural systems sustained by values, memory, and local governance.

Recognition Status: L’Horta de València has received widespread regional, national, and international recognition, including its designation as a GIAHS site by FAO (2019) and the listing of its traditional Water Tribunal as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage (2009). Additionally, it benefits from legal protection under Spanish and Valencian law, and is integrated into European and global food and landscape networks.

In contrast, the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS), though rich in traditional knowledge and hydrological innovation, has not yet achieved formal global recognition. However, some components, particularly the Kuhl irrigation system, have been acknowledged at national and academic levels for their heritage and sustainability value. This includes state-led heritage recognition and policy interest in sustainable mountain agriculture.

Table 8: Comparative Overview of the Recognition Frameworks of L’Horta de València and the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS)

| Recognition Level | L’Horta de València (Spain) | Kangra Agricultural System (India) |

| 1. International Recognition (FAO-GIAHS) | Designated as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) by FAO in 2019, recognizing its historic irrigation network (acequias), agrobiodiversity, and cultural landscapes. | Not Yet Proposed |

| 2. UNESCO World Heritage | Proposed as a Cultural Landscape; supported by local institutions advocating for World Heritage inscription due to its integration of natural and cultural elements. | Not yet proposed for UNESCO designation; currently lacks formal global cultural or landscape heritage status. |

| 3. National Recognition | Recognized under the Bien de Interés Cultural (BIC) status for specific elements such as irrigation canals, mills, and the Water Tribunal. | GI Tag for Kangra Tea(2005), Kangra Painting(2010), Proposal for Declaring certain areas as Geo Heritage of India. |

| 4. Spatial Planning Integration | Covered under the Plan de Acción Territorial de l’Horta (PATH), which defines land-use zoning, restricts urbanization, and promotes agro ecological corridors. | No formal territorial planning mechanisms or zoning frameworks to conserve the agricultural matrix or prevent land-use change. |

| 5. Documentation and Mapping | Extensively documented through historical, hydrological, and spatial studies. Official GIS databases and legal boundaries exist for irrigation infrastructure. | Documentation efforts are ongoing; however, most Kuhls remain unmapped due to their fragmented and small-scale nature. Historical records are largely narrative and dispersed. |

| 6. Tourism and Cultural Promotion | Actively promoted through agro-tourism, cultural routes, and educational programs centered on irrigation heritage and local produce. | Cultural tourism potential remains untapped. Agricultural landscapes and water channels are not yet integrated into tourism or heritage circuits. |

Conclusion

The Kangra Agricultural System (KAS) in Himachal Pradesh and the L’Horta de València in Spain represent two of the world’s oldest farmer-managed irrigation systems, each showcasing distinct yet resilient water engineering strategies adapted to their unique geographical and climatic contexts. KAS spans an area of approximately 336 km² and supports a large agrarian population of around 500,000, primarily dependent on agriculture. In contrast, L’Horta de València, covering merely 17 km², serves a small yet aging population, with over 60% aged above 55, engaged in agriculture, fisheries, and increasingly in peri-urban tourism and services.

The engineering backbone of KAS lies in its Kuhls—gravity-fed, glacier-fed surface channels constructed and maintained by local watermen known as Kohli. These channels follow the natural topography with moderate slopes and distribute snowmelt and rain-fed river water across terraced landscapes. This decentralized, community-managed irrigation relies on informal customary rules and shared responsibility for channel maintenance. There is no pumping allowed upstream, and each field irrigates in sequence, maintaining downstream equity.

On the other hand, the L’Horta irrigation system exemplifies medieval hydraulic engineering with strong Arabic and Roman influences. It is centered on a highly structured and legally enforced gravity irrigation network, includes eight major canals—Rovella, Favara, Mislata-Xirivella, Quart-Benàger-Faitanar, Tormos, Rascanya, Mestalla, and the Real Acequia de Moncada—that branch hierarchically into a comb-like structure via partidors (flow splitters) and sluice gates, ensuring equitable and efficient water distribution. The system is governed by the Tribunal de las Aguas, the oldest water court in continuous operation, which enforces rotational water use and resolves disputes. Excess water from higher elevations is efficiently reused at lower levels, culminating in the Albufera wetlands, which form a crucial ecological buffer against Mediterranean droughts and floods.

Both systems operate without reliance on modern mechanical pumps, instead utilizing natural slopes and communal knowledge systems. Yet, KAS remains highly decentralized and adaptive to mountainous terrain, while L’Horta reflects a more codified, institutionally protected, and technically engineered model suited to flat alluvial plains. Their co-evolution illustrates how traditional water systems can embody ecological sustainability, technical ingenuity, and social governance rooted in cultural heritage.

Proposal for inclusion in GIAHS List

Name of Agriculture System: Kangra Agriculture System (KAS). Kangra Plains are also termed as Kangra Outwash Plain, Kanga Re-entrant and Kangra Alluvial Fans.

Location : Located on 32.18308393795139, 76.33280343475678 District Kangra, Himachal Pradesh India.

The site is located on the southern slope of Dhauladhar mountain range (Part of lesser Himalaya). The entire agricultural system falls in the Beas River Basin.

Accessibility of the site to capital city or major cities:

Road : Site is well connected by Mandi- Pathankot National highway, Shimla – Dharamshala National highway and Chandigarh -Kangra National highway.

Air: Gaggal Airport is located in the midst of Kangra Agriculture System.

Railway : Mandi -Joginder Nagar railway line passes from Kangra Agriculture system.

Waterways: Not Available.

Approximate Surface Area: 43500 hectare.

Agro-Ecological Zone:Western Himalayas, Warm Sub humid (To Humid With Inclusion of Per humid) Eco region(1) .

Topographic Features: Average Elevation range from 600 mtr-1500 Mtr

Climate Type: Wet Temperate Climate

Approximate Population:18 Lakh

Main Source of Livelihoods: Agriculture

Ethnicity/Indigenous population: The majority of the population belongs to the Indo -Aryan ethnicity and People of Ghirt community constitute the main agriculture community.

The Summary Information of the Agricultural Heritage System: Kangra Agricultural System is composed of three elements namely:- (1) “Outwash Plains (2) Kuhls (3) Complex Social & Cultural System.

Kangra outwash plains also known as Kangra Alluvial Fans are located between Lesser Himalaya (4300 Mtr) and Shiwalik (900 Mtr). Geologically these plains are believed to be one of the largest “Outwash Plains” of Himalaya. These plains are the result of Ice ages followed by intense monsoonal phases. These plains are also unique in the sense that they have preserved the “Climatic and Geological” record of Earth history.

Kuhls is a man-made gravity driven irrigation network originating on the Southern slope of Himalaya. The history of Kuhls system can be traced back to Medieval India. Each village and each Agri field possesses its own Kuhl ,the length of some of these Kuhl is between 25-50 km. Kuhls also have changed the regional landscape.

Kuhls are completely managed by local villagers with little assistance from local authorities .A village level committee oversees the overall management and function of Kuhls. Riwaj-i-Abpashi a19th century British Era text defines and regulates the overall functioning of Kuhls. However it is the Oral law and Customs that bind all users with Kuhls. Proper functioning of Kuhls required joint efforts and coordination among the people and villages.

Description of Proposed GIAHS site

Three Main components of System are:

A) Kangra Outwash Plains, B) Kuhls, C) Community Management.

(A) Kangra Outwash Plains The Himalayas began forming around 65 million years ago (MYA) and continue to evolve due to ongoing tectonic activity. The Greater Himalayas, marking the primary collision zone, feature high peaks, deep valleys, and glaciers, with sparse human habitation. South of this, the Lesser Himalayas lie at a relatively lower altitude, receiving substantial snowfall and rainfall, which support moderate to dense human populations. Further south, the Shivalik Hills, a low-elevation zone, lack snow cover but play a crucial role in sediment deposition.

The Kangra Basin’s sedimentation commenced approximately 11 MYA, ceasing in the Upper Shivaliks around 200 KA (thousand years ago). By 100 KA, an Outwash Fan began forming, depositing vast amounts of glacial and fluvial sediments (Srivastava, Rajak, and Singh, 2009).

The proposed Kangra Agricultural Heritage System (KAS) site is situated between the Lesser Himalayas (north) and the Shivalik range (south). It is bounded by two major thrust faults:

– Main Boundary Thrust (MBT) in the north, and Jwalamukhi Thrust (JMT) in the south.

This has resulted in a large synclinal basin, primarily composed of debris from the Dhauladhar Range, forming the largest outwash plain in the Himalayas (Srivastava et al., 2009). Geological processes, including MBT and JMT activity, Ice Age glaciation, and intensified monsoonal phases, have played a key role in shaping this landscape.

The Kangra Outwash Plains are geologically unique and significant, providing valuable insights into Earth’s geological and climatic history. More importantly, these plains have given rise to highly fertile alluvial soils, which, combined with the traditional Kuhl irrigation system, sustain diverse agricultural practices (Srivastava, Rajak, and Singh, 2009). This interplay of geology, climate, and human adaptation forms the foundation of Kangra resilient agrarian heritage, warranting its recognition as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS).

( “Wah Tea Estate – Since 1857 | A Legacy of Kangra Tea Cultivation Amidst Ice Age Moraines” Image Represent the rich Geological, Cultural and Agricultural Heritage of the region” )

(Terrace Farm: Gentle sloping plains are cut into Terrace Farm, which prevents soil erosion. Beginning from the foothills of Dhauladhar, these plains slope gently toward south.)

( Glacier erratics spread in Agrifield, add unique Geological perspective to regional Landscape)

(B) Kuhl System. Kangra plains are characterized by a dense river network, originating from snow-clad Dhauladhar mountain range. Kuhls are channeled from these rivers and diverted into plains, Kuhls are then further subdivided into numerous small sub Kuhls for irrigation purposes. Gentle slopes of plains provide gravitational energy to flow the water. There are approximately 715 large kuhls and around 2500 small kuhls (Baker, 1994).

( Dense River Network in Outwash Plains, SRTM 30m resolution, Strahler Order 5 River )

Density (D) is calculated as: D = L/A , D = 824.720/435 = 1.89 km/Sq.km

Where:

• D = River density (km/km2)

• L = Total length of river channels (km)

• A = Study area (km2)

“Kuhl ” began with construction of “Danga ” across the river, Danga is made of river Stone, Soil and Grasses.

“Kuhl” ,the main water channel is permanent in nature, these kuhls are dug out with greater effort after a careful survey of the field.Construction of “Big Kuhl”was sponsored by local kings, whereas small Kuhls were constructed by local farmers without state help. “Tap” is the point from where Kuhls are further bifurcated into small Kuhls.The South Western monsoon is strong enough to destroy the Danga so after every monsoon, Danga either has to be re- constructed or repaired.

The Kuhl irrigation system in Kangra has sustained agriculture for centuries through community-managed water channels. A notable example is the Bhawarna Wali Kuhl, built by Kirpal Chand, younger brother of Bhim Chand. Originating from the Dhauladhar mountains above Bandla, it is the longest Kuhl in Kangra District,showcasing advanced indigenous hydraulic engineering. Historically, Kuhls were maintained through community-led governance, ensuring equitable water distribution

( C) Community Management

The Kuhl irrigation system is the traditionally, community-managed network that supports local agriculture. Following the onset of British rule in 1846, significant changes occurred, including the introduction of a new revenue system and the formalization of existing local laws and customs. First formal documentation of irrigation practices, known as the “Ribaj-i-Abpashi,” was issued in 1874 and later updated in 1915 (Baker, Marker J., 1994, 2001). The management of the Kuhls rests with a village-level committee, which designates a Kohli (waterman) responsible for key tasks such as regulating water distribution, scheduling water releases, maintaining the Kuhl channels, and resolving disputes. (Source: Death of Kuhl Irrigation System of Kangra Valley of Himachal Pradesh: Institutional Arrangements and Technological Options for Revival). After independence, the responsibilities traditionally held by the Kuhl Committee were gradually given to government authorities.

Characteristics of Proposed GIAHS

(3.1) Food and Livelihood Security:

Western Himalaya is home to roughly 53 million people. The population of the State of Himachal Pradesh is roughly 7 Million, whereas the Population of the Proposed site is 439942 . Kangra District is predominantly rural, with 94.3% of its population living in rural areas. Agriculture is the backbone of the economy, with 44.9% of the workforce engaged in cultivating the land. The high percentage of cultivators (303,007) and the continued reliance on traditional farming practices, such as the Kuhl irrigation system, underscores the importance of preserving these agricultural heritage practices.

The relatively small urban population (5.7%) and small industrial workforce (2.3%) suggest that the district is largely agrarian with limited urbanization. However, the presence of 271,414 female workers in the workforce is noteworthy, indicating a level of gender inclusivity, especially in rural agriculture. Additionally, the 12.77% growth rate in population over the last decade reflects the district’s steady demographic expansion, which will have implications for future agricultural production, workforce needs, and infrastructure development. Kangra’s projected population of 17.35 lakh by 2022 signifies that the region’s agricultural systems will face increasing pressures to meet the demands of both the local population and the growing tourism sector. This makes the sustainable management of agriculture even more important in the coming years. The relatively small industrial base indicates an opportunity to integrate agro-based industries and rural entrepreneurship, potentially adding value to the agricultural products and providing alternative livelihoods while maintaining the region’s agricultural heritage.

( Rice Field in monsoon , near Nagrota Bagwan, KAS site fall in Leeward side of Dhauladhar and received intense rainfall throughout the years. )

Tehsil wise Population in Tehsil fall in KAS:

| Tehsil | Population |

| Baijnath | 95,229 |

| Dharamsala | 1,36,536 |

| Dheera (S.T.) | 22,119 |

| Jaisinghpur | 61,082 |

| Kangra | 97,568 |

| Nagrota Bagwan | 76,899 |

| Palampur | 1,89,276 |

| Shahpur | 67,758 |

| Thural (S.T.) | 19,287 |

| Total | 4,39,942 |

District Demography:

| District | Projected Population by Census 2022, in lakh | Total Workers | Male Workers | Female workers | Cultivator | Agriculture | Industries |

| Kangra | 17.35 | 675170 | 403756 | 271414 | 303007 | 54849 | 15662 |

Kao -Kalath. – It is a “traditional barter exchange system” which defines the economic relation among the different castes. For example:- Village Metalsmith provides the tools to farmers in exchange of processed and unprocessed Food (Kao is Processed/Kalath is unprocessed), village Potter maker provides essential utensils and similarly arrangement of Bamboo articles is made in exchange of Food Grains.

Tribesman: Apart from this, the hill tribesmen, locally known as the Gaddi, traditionally migrate between the high-altitude mountain ranges of the Dhauladhars and the fertile plains. In the lower valleys, they engage in a barter economy, exchanging wool, sheep, and goats with local farmers in return for grains and other essentials. This symbiotic relationship has shaped both the cultural fabric and agro-ecological balance of the region for generations.

( Sheep herds of Transhumance Gaddi)

Tourism: Beauty of mosaic landscape attracts thousands of Tourists from all over the world. The landscape is dotted with Tea Garden, Ancient Forts ,Temples and Buddhist Monasteries, Mountain Passes, Rivers etc.It plays a pivotal role in the region’s socio-economic and cultural fabric, enhancing the appeal of its agricultural landscape. In 2024, a total of 774,440 Indian tourists and 26,195 foreign tourists visited the region, with peak tourist activity recorded in March (136,066 total tourists), May (83,388 total tourists), and December (85,480 total tourists). This influx of visitors not only boosts the local economy by supporting rural livelihoods, such as through hospitality services, homestays, and handicrafts, but also helps raise awareness about the importance of preserving the region’s rich agricultural and cultural heritage.

( Bir near Baijnath is Asia’s Highest Paragliding Site, Dhauladhar Mountain range in Background )

The Gharat: It is a water energy-driven mechanism that functions entirely without electricity, making it highly sustainable and eco-friendly. Historically, these mills served as vital community assets, contributing to the local economy by providing grain processing services and employment to mill operators, known as Gharatias. They also acted as community gathering points, where local knowledge, traditions, and social ties were reinforced.

(Traditional flour Mills largely depends upon Kuhl Networks)

(3.2) Agro Biodiversity:- Agrobiodiversity refers to the variety of plants, animals, and microorganisms involved in agriculture and food production. In the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS), this diversity plays a crucial role in maintaining agricultural productivity, resilience, and sustainability. The KAS is home to a broad spectrum of crops, livestock, and other species, all cultivated using traditional farming methods that are well-suited to the region’s mountainous landscape. This rich agrobiodiversity is essential for local food security, the resilience of farming systems, and the overall sustainability of the ecosystem.

The crop diversity in KAS includes cereals and grains such as wheat, maize, barley, and rice, alongside traditional millets like Bajra, Finger Millet (Kodra), and Great Millet (Jowar), all of which are adapted to the region’s diverse soil and climate conditions. Additionally, oilseeds such as sesame (Til), mustard (Rai), and fenugreek (Mithra) are grown, along with legumes like gram (Chhola) and pigeon pea (Arhar), which help enrich the soil with nitrogen, contributing to soil fertility. Vegetables like brinjal (Baingon), cucumber (Khira), and bottle gourd (Gandoli) are commonly cultivated, as are fruits like melon (Kharbuza) and cardamom (Tlaichi).

The livestock diversity in KAS is also notable, with local breeds of cows, buffaloes, goats, and poultry that are well adapted to the terrain and climate of the region. These animals play an important role in both food production and the local economy. Furthermore, the surrounding forests provide a variety of wild species that are vital for ecosystem balance, including medicinal plants, wild herbs, and pollinators like bees, which are essential for the pollination of crops.

Rice Cultivation:- Kangra cultural traditions reflect deep-rooted religious and medicinal practices. Historical records mention the Devi temple in Bhawan, where devotees practiced self-inflicted tongue cutting, believing it would be miraculously restored within hours or days. This ritual, though rare today, signifies the region’s enduring spiritual customs. Additionally, during Akbar’s reign (1556-1605 AD.) Kangra was renowned for four distinct things: surgical nose reconstruction, eye disease treatments, Basmati rice cultivation, and its strong fort—highlighting its expertise in medicine, agriculture, and defense (Gazetteer of the Kangra District, 1883-84, Government of Punjab, n.d., p. 67).

( Various Rice seed varieties Developed by Rice and Wheat Research Station)

( Left to Right , White Crane flying over wheat field, White crane in Kuhl, Dragon Fly and Wooden Apple)

Wheat Cultivation:-Wheat cultivation forms a vital component of the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS), particularly as a major rabi (winter) crop grown between November and April. Following the kharif season rice harvest, wheat is sown utilizing residual soil moisture and the age-old Kuhl irrigation network. The region’s agro ecological conditions—moderate winter temperatures, fertile alluvial soils, and occasional winter rains—create a conducive environment for wheat production. The region was in ancient times known for its rich rice cultural heritage, and it is often said that 365 varieties of rice are there and so the clan of Girth people. Such phrases emphasize the local community’s connection with nature.

Kangra Tea:- Kangra Tea represents a vital component of the agricultural and cultural landscape of the Kangra district in Himachal Pradesh. Introduced by British colonialists in the mid-19th century, this tea variety has become synonymous with the identity of the region. Cultivated on the terraced slopes of the Dhauladhar foothills at elevations ranging from 900 to 1,400 meters, Kangra Tea benefits from the area’s unique agro-climatic conditions, including cool temperatures and well-drained, slightly acidic soils. These environmental factors, combined with traditional cultivation and processing techniques, impart the tea with its distinct light liquor, floral aroma, and subtle muscatel flavor.

Unlike the more robust teas from Assam or the sharp notes of Darjeeling, Kangra Tea is valued for its mild yet complex flavor profile, making it highly sought after in niche markets. Historically, the tea has garnered international recognition, receiving accolades at various global exhibitions. In contemporary times, the conferment of the Geographical Indication (GI) tag has further elevated the tea’s status, promoting its significance as an agroecological and economic asset.

( Tea Garden in Winter, 2024 near Jia Valley)

Kangra Tea not only contributes to the region’s “agrobiodiversity but also plays an integral role in sustaining traditional livelihoods”. Many smallholder farmers continue to cultivate tea using environmentally sustainable methods, thereby reinforcing the cultural and ecological resilience.. The tea gardens, interspersed with indigenous flora, also serve as habitats for various pollinators and bird species, enhancing the ecological fabric of the region.

| Year | Event | Notes |

| 1830s | Early Tea Cultivation in India | Tea cultivation experiments begin in Assam after indigenous tea plants are discovered. Assam, Cachar, and Darjeeling emerged as early tea-growing regions. |

| 1850 | Introduction of Tea in Kangra | British botanist Dr. William Jameson introduces tea plants from Kumaon to Kangra. Nurseries are set up in Nagrota and Bhawarna at 3,300 ft elevation. |

| 1852-1860 | Government Tea Plantation at Holta | Lord Dalhousie establishes a government tea plantation at Holta (4,200 ft). Free tea seeds are distributed to locals, encouraging private tea farming. |

| 1867-1868 | Success and Growth | Large-scale tea plantations flourish. The barren landscape transforms into organized tea gardens with homes, factories, and infrastructure, cementing Kangra as a tea-producing hub. |

Litchi Cultivation: Outwash Plains offers ideal conditions for lychee (Litchi chinensis) cultivation. Grown predominantly in the lower elevations of Kangra outwash plains and foothill regions, lychee thrives in the valley’s subtropical climate, characterized by warm summers, adequate monsoon rainfall, and moderate winters. Traditionally cultivated in homestead gardens and community orchards, lychee holds both nutritional and economic significance for rural households.

Bee Keeping: A significant turning point in Kangra beekeeping history occurred in 1964 with the successful introduction of the European honeybee (Apis mellifera) at the Kangra Beekeeping Station. Utilizing the inter-specific queen introduction technique, A. mellifera queens were integrated into Apis cerana colonies, laying the foundation for scientific beekeeping practices in India. This innovation significantly improved honey yields, as A. mellifera is known to produce substantially more honey compared to the native A. cerana.

( India’s Oldest Bee Research station, Nagrota Bagwan)

(3.3) Local and Traditional Knowledge System:- Local agriculture system has produced excellent traditional Knowledge systems ranging from using, Water Resources, Soil management, Seed Preservation, post harvest management etc.

Development of Kuhls: The KAS site lies within the Himalayan Foreland Basin, adjacent to the Dhauladhar Range. It is characterized by a sequence of fluvial terraces formed during the Late Pleistocene to Holocene due to tectonic uplift, sediment aggradation, and periodic incision by rivers. The terraces identified in the digital elevation model can be categorized into three orders:

- T1 (Upper terraces): Older terraces, higher in elevation, and farther from active river channels.

- T2 (Intermediate terraces): Formed by intermediate stages of river incision, often used for gravity-fed irrigation.

- T3 (Lower terraces): Recent formations closer to the current riverbed, composed of finer alluvium and more frequently cultivated.These terraces are spatially aligned with the natural slope and water drainage system of the region.

( Left Image showing the Kuhls and river Terrace , right hand image showing the Kuhls course along the river descent)

The Kuhl irrigation system is constructed by diverting water from perennial streams, which are sourced from glacial melt. The key steps in the development process include:

Diversion Point Selection: The intake is located at higher elevations where water from snow-fed rivers can be diverted by gravity.

Weir Construction: A temporary diversion structure (locally called Danga) is made using stone, brushwood, and mud to redirect flow into the Kuhl.

Channel Excavation: The main channel is dug manually along the contour line to ensure a gradual slope, maintaining laminar flow.

Structural Reinforcement: Steep or erosion-prone sections are stabilized using stone linings and retaining walls.

Branch Distribution: Water is distributed from the main Kuhl into branch channels reaching individual fields. These are regulated through bunds and small gates.

Community Management: Construction and maintenance of Kuhls are performed collectively, with coordination by village institutions or local leadership.

This design allows irrigation to function effectively in sloped and terraced terrain without mechanical pumping.

( Two Sub Kuhls bifurcating from main Kuhls, Top right and bottom Left showing the course river in forest and Bottom right image showing , water channelisation from main river)

Spatial Integration: Kuhl channels (marked in red) are closely aligned with contour lines, maintaining a near-uniform slope from the river source (marked in blue). This design achieves several technical outcomes: Efficient Gravity Flow: Minimal energy is required for water movement.

Erosion Control: Low gradient flow reduces channel degradation.Multi-Terrace Irrigation: Kuhls are capable of servicing multiple terrace levels through minor branching systems.These features collectively enhance water delivery reliability and system longevity.

(Top image show Kuhl crossing the National Highways near Parror, Left Hand side: Govt funding toward construction of new Kuhls , Right Hand side: Kuhl crossing National Highway near 61 Mile)

Land Management: Kangra tea plantations are carefully situated within the altitudinal range of 2,500 to 5,000 feet, where the microclimatic conditions favor slow leaf maturation, enhancing the tea’s flavor. Unlike large-scale tea estates in Assam or the Nilgiris, Kangra planters have historically adopted a small and controlled plantation model. This limited land expansion strategy has prevented the excessive deforestation and land degradation that often accompany large-scale monocultures. Furthermore, the region’s undulating terrain is selectively utilized, avoiding excessively steep slopes to minimize soil erosion and runoff.

Kural/Kurli: Local Monsoon Season Classification.

Bamboo:Bamboo is an integral part of the KAS system. From providing basic agriculture tools to storage, it plays a crucial role in the system.

( Village woman making baskets from Bamboo)

Management of Fodder: – Following the harvest, straw is gathered and shaped into large, dome-like heaps called “Kuhada,” an age-old method of preserving fodder for livestock during the lean winter months. These structures are strategically placed on the margins of terraced fields, ensuring easy accessibility for local farmers while optimizing the use of post-harvest land.

(A post-harvest panorama of the Kangra Agricultural System, showcasing terraced valley fields framed by the Dhauladhar ranges. The clustered haystacks reflect indigenous fodder conservation, while the fragmented plots and bunded fields illustrate smallholder, multi-crop subsistence farming. This landscape exemplifies the integration of agriculture, ecology, and community through gravity-fed Kuhl irrigation, agroforestry, and organic soil care—hallmarks of a resilient, living heritage deserving GIAHS recognition.)

(3.4) Culture, Value System and Social Organisation:

As early as 200 BC a rare bilingual inscription(Popularly Known as Pathiyar inscription) written in Brahmi and Kharosthi, mention the existence of “Community Pond “ , in midst of Paddy field near Nagrota Bagwan, Similarly another inscription dated roughly around 100 AD mentions the existence of “Grove ” near Dharamshala. Both inscriptions are located in Paddy field and protected by the Archeological Survey of India.

(Left :200 BCE. Pathiyar Inscription, Nagrota Bagwan, District Kangra mention the existence of community Pond, Right :Khaniyara Inscription, 100 AD mention the existence of Grove)

Kangra Painting:- 17th century Kangra School of Painting (GI Tag) vividly captures the unique beauty of landscape. Impact of local Landform on the artist mind is reflected in the use of colors, vividness and depiction of local weather.

( Kangra Painting vividly Capture the regional Landscape and natural ethos)

Sair Festival:- Sair festival is celebrated with Local Holiday. In Sair, farm produce is offered to Devta(God) and a variety of cuisines are prepared. Sair marked the beginning of harvesting of new crops.

( Agriculture Produce offered to local God during Sair Festival, )

Role of Devta:- Annual visit to Naag(snake deity) Temple. Offering Rot(Roti made of Wheat) the Sidh Shrine and first milk of cow to Kulj are important rituals of the agricultural community.

Music and Folklore:-Kuhls are an integral part of villager’s lives. Numerous songs and Folklore are surrounded around the Kuhls.The traditional folk songs and oral poetry vividly express the connection of local communities with their environment. A popular line echoes across the valley:

“Thandi thandi hawa jhuldi,

Oh jhulde chila de,

Dalu jeena Kangre da……………………..“

English translation “ (The cool, gentle breeze sways,

Oh, it sways through the pine trees,

I cherish the life of Kangra………………..)”

This folk expression poetically captures the essence of Kangra’s traditional houses, where wooden balconies (jeena) sway gently in the cool breeze passing through the towering Chila (Salix trees) and lush terraces. Such oral traditions are deeply rooted in the daily lives of Kangra’s inhabitants, embodying their emotional and spiritual bond with the landscape.

Kangri Dham: Kangri Dham is a traditional multi-course vegetarian feast that forms a vital part of the cultural identity and agro-culinary heritage of Himachal Pradesh, especially in the Kangra region. Deeply rooted in the agrarian traditions of the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS), Kangri Dham reflects the intimate connection between local agriculture, food practices, and cultural expressions

Pottery: Kangra Agriculture System is not only agriculturally significant but also known for its rich tradition of earthenware pottery. This local craft, passed down through generations of Kumhar (potter) communities, reflects the symbiotic relationship between natural resources, rural livelihoods, and cultural identity—making it an important intangible component of the Kangra Agricultural System (KAS).

( Pottery is essential part of KAS , traditionally potter provide the earthen utensils in exchange of grains)

3.5) Remarkable landscapes, land and water resources management features: The Kangra region stands as a testament to the harmonious interplay between nature and traditional agricultural practices. G.C. Barnes, who served as the Settlement Officer of Kangra in the 19th century, eloquently captured this balance when he remarked,

“No scenery in my opinion presents such sublime and delightful contrasts. On the one hand, the eternal snow and rugged grandeur of the Dhauladhar, on the other, the smiling and well-cultivated valleys of Kangra, watered by the streams which derive their sources from those very glaciers whose vicinity renders the temperature of the valley so pleasant and enjoyable.”

This statement perfectly encapsulates the region’s distinctive combination of natural beauty, climatic advantage, and agricultural productivity.

The Kangra Outwash Plain, the largest such plain in the Himalayas, further exemplifies this unique landscape. Its geomorphological formation is intrinsically tied to the tectonic evolution of the Himalayan range, making its presence at such an altitude a remarkable geological and ecological feature. The gently sloping terrain of the outwash plain is intricately shaped by terraced farming systems, enhancing both the utility and aesthetic value of the landscape.

(The Kangra Valley Railway, established in 1929 during the British era, is a heritage marvel that traverses the breathtaking Dhauladhar ranges, Picturesque rice field, and historically rich landscapes)

Kuhls : A key component of Kangra’s land and water resource management is the traditional kuhl irrigation system. These unlined earthen channels, fed by glacial and stream waters from the Dhauladhar range, are designed to allow controlled seepage. As water travels through the kuhls toward agricultural fields, it gradually infiltrates the surrounding soil, contributing significantly to the recharge of shallow aquifers and sub-surface groundwater reservoirs. This sustainable water management system has underpinned agricultural resilience in the region for centuries and is a living example of Indigenous knowledge aligned with ecological principles.

This synthesis of spectacular natural features with human ingenuity in land and water management directly corresponds with the Remarkable Landscapes, Cultural, and Aesthetic Values criteria of GIAHS.

Wettest Place of Western Himalaya: Kangra Valley unique landscape makes it Wettest Place of Western Himalaya.The steep gradient of the Dhauladhar range plays a crucial role in inducing strong orographic rainfall in the region. As the moist monsoon winds from the south ascend abruptly against the Dhauladhar, the air cools rapidly, resulting in intense precipitation on the southern slopes. The Dhauladhar, acting as the primary mountain barrier in the Western Himalayas, enhances this orographic effect. This phenomenon is particularly prominent in areas near Dhauladhar, which receive exceptionally high rainfall, feeding the numerous streams and glaciers that sustain the traditional irrigation and agricultural systems of the Kangra Valley.

(4 ) Threat and Challenges to Proposed GIAHS sites

KAS is threatened by climate change (reducing stream flows), rural-urban migration, and weakening of traditional knowledge systems. The degradation of Kuhls due to lack of maintenance and encroachment is accelerating. Recognition of Sites under the GIAHS framework can protect , climate resilient centuries old Agricultural system.